Intern Weekly Response: Museums and Neutrality

Every week we’re asking our summer interns to share some thoughts and responses to various experiences and readings. This week we asked them to read a pair of articles by Gretchen Jennings on museum neutrality and find a third related article to explore and reflect on. To read more posts from JMM interns, past and present, click here.

The two articles presented were “The Idea of Museum Neutrality: Where Did it Come From?” and “Thoughts on Museum Neutrality: A Question of Balance.”

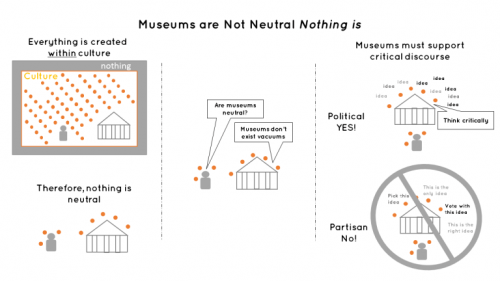

“Museums are Not Neutral. Nothing is Neutral.”

-Intern Cara Bennet

As Gretchen Jennings notes in her blog post, the debates surrounding museum neutrality are complex and often revolve around how we define “neutral.” Museum professional Seema Rao joins the debate in her blog post “Are Museums Neutral? Or are they Neutered?” Rao argues that any choice a museum makes negates its neutrality. Museums reveal bias in the items they choose to collect, the stories they choose to tell, and the way they choose to tell them. Rao explains that “Any history is based on decision and interpretation. When you present that history, you are supporting those decisions. You might not see those decisions. You might believe those ideas to be facts, but assuredly, other facts have been left out.”

The objects and stories that are excluded say just as much about a museum’s biases and values as the objects and stories it includes. Instead of striving for the unattainable goal of neutrality, museums should strive for balance. By acknowledging that there are multiple perspectives to every story, museums can become spaces for critical discourse. Museums can educate visitors just as much by challenging their perspectives and sparking conversations as they can by teaching them facts.

Cara selected “Are Museums Neutral? Or are they Neutered?” By Seema Rao as her third article.

“Choosing the Story:

-Intern Alexia Orengo Green

When a curator chooses the pieces that are going to be exhibit, the curator selects how the story is going to be told. The curator must choose which artifacts contribute more to the story that is intended to be told. If there is something that impacted me from the first article by Gretchen Jennings regarding museum neutrality was her definition of “neutral”. Jennings writes: “Perhaps what neutral means is “normative,” i.e museums should reflect and represent-but not question-what already exists.” This definition made me a little uncomfortable because as a history major, my professors have taught me to question what we know, to ask who, what, and why constantly. By questioning what we know, we can learn new things and discover new narratives.

I believe that museums should display what we know and challenge the visitor just as the Eastern State Penitentiary did. Their exhibit regarding mass incarceration in the United States as is showed on the third article I selected, interacts with the visitor by putting him or her in a “thought-provoking” position. By doing this, the visitors are neutral while learning about a new topic while at the same time questioning what they thought they knew. This notion also goes with Jennings second article in which she concludes that the new trend of needing museums to give a sense of “closure” takes away the neutrality.

In the museum world as it can be seen with these three articles the topic of neutrality is important. As an intern, I believe the best way to be neutral is to research and look at the evidence in a non-bias way. By doing this, one can notice details that would not have seen otherwise. The museums’ work is to take the evidence that was gather and create a narrative that engages and challenges the public. The museums’ work is not to give “closure” to the visitor like Jennings said or to only represent what we already know.

Alexia selected Merritt, Elizabeth. “Beyond Neutrality.” American Alliance of Museums, Center for the Future of Museums Blog. August 23, 2016 as her third article.

“Intentional Non-Neutrality”

-Intern Marisa Shultz

To speak of my experience in the history classrooms of my upbringing is to speak of dates, names, trade routes, maps, wars, and amendments — namely a factual foundation, the who, what, when, where, and sometimes why. To speak of my experience in college is to speak of debate, engaging research, and dissecting the perspectives of other historians — namely, interpretation, or how we choose to understand and remember historical figures and events. While the former provided the necessary knowledge and information, the latter challenged me to understand history as commentary; time and time again, historians engage in intellectual battles over how a particular figure or event should be remembered.

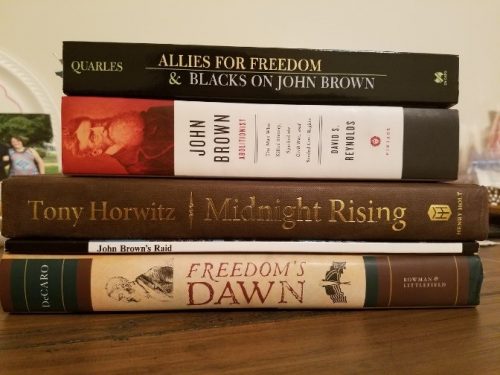

Let me give you an example: John Brown, one of the most controversial figures from Antebellum Untied States. In 1859, Brown led a raid on a Federal Armory in Harpers Ferry in what is now West Virginia. Brown’s goal was to encourage slave uprisings in the local area, and to secede from the union to make a slavery-free country. Ever since Brown was captured and hanged that very year, historians have debated almost every aspect of Brown’s life, and have depicted him as a martyr, a terrorist, a religious zealot, a delusional lunatic, and a desperate man looking to make a lasting mark on history. In these interpretations of Brown’s life, he was still a failed businessman, the head of his family, and the raider of the armory. These facts do not change, but the interpretation does. This is the core of historical debate and controversy.

Okay, so how does any of this relate to the questions surrounding museum neutrality? What I found so fascinating about the articles “The Idea of Museum of Neutrality: Where Did It Come From?” and “Thoughts on Museum Neutrality: A Question of Balance” is how they defined museum neutrality. Gretchen Jennings distances museum neutrality from “accuracy and… well-researched conclusions.” Rather, to Jennings, museum neutrality has the “connot[ation] of non-involvement, nonendorsement of any view.” Dan Spock on the other hand strikes a slightly different chord when he argues that museums should seek a balance in historical perspective – “acknowledg[ing] the absent narrations in the historical record”. For both of these individuals it is the presentation and interpretation of the exhibit topic that raises the ethical dilemma – should we recognize, allow, and even promote these interpretations, or should we not take a side in the historical debate? Both Jennings and Spock argue that it is essential to acknowledge and curate specific interpretations that are supported by factual evidence and strong research, as many of the historians of Brown have done in written form.

I was curious as to how like-minded museums were incorporating this concept into their exhibits, so I turned to Dr. David Flemming of the International Museum of Slavery in Liverpool, England. Flemming, in the article “Museums Taking Stand for Human Rights, Rejecting ‘Neutrality’” described that “you can’t dictate to people what they’re going to think or how they’re going to react. But you can create an atmosphere.” A museum cannot force its visitors to understand the artifacts and narrative in a particular way, but it can portray a particular interpretation, and thus help guide their visitors to potential conclusions. What is so essential here is that Flemming and the museum’s staff have determined their interpretation and have intentionally curated and designed exhibits and programs around the message and lesson they want to promote. It is this intentional non-neutrality, that is trying to leave the visitors with a call to action, that will undoubtedly influence and positively challenge its visitors.

Marisa chose “Museums Taking Stand for Human Rights, Rejecting ‘Neutrality’” by A. D. McKenzie for her third article.

“Objects Tell Stories”

-Intern Ellie Smith

Traditionally museums have been looked at as places where history and facts are displayed. But the reality of how museums function is much more complicated. Museums are responsible for displaying objects that have great cultural significance to many individuals and groups of people. These objects can tell the stories of people whose voices have been marginalized and ignored. By claiming impartiality or neutrality museums can avoid approaching difficult and controversial topics. But if the history of the object being displayed is controversial then it should be the museum’s job to present an accurate history of the object. Museums are spaces where challenging topics can be discussed in an informative and accurate way.

Museum neutrality raises the issue of what objects are being displayed. Displays themselves are inherently biased because the objects have to be chosen by curatorial staff. Some objects make the cut and others do not. The objects that are being displayed have voices all their own but some voices are being heard over others. Based on what objects are being displayed a different version of history is being told.

The significance of each object also changes depending on who is viewing the display. Objects from specific cultural or religious locations will represent something different to a member of that group verses to another museum patron. An object that is deeply meaningful to one group maybe considered unimportant to others. If the object is not considered important it will not be displayed and that story is lost. The differing views on objects also changes whose story is being told. Objects are not just things; they are the link to people of the past. These people had unique stories and lives. In order to do objects justice, we must tell the whole, albeit sometimes difficult story. Museums can no longer ignore objects with controversial or challenging histories. History is constantly being rewritten based on new information and research. Museums need to reconsider the history of their collections and include objects that challenge visitors to think about the past and its relationship to the present and the future.

Ellie chose Mark Busse’s “Museums and the Things in Them Should Be Alive” as her third article. Full citation: Busse, M. (2008). Museums and the Things in Them Should Be Alive. International Journal of Cultural Property, 15(2), 189-200. doi:10.1017/S0940739108080132

“Accurate, Balanced, and Questioning”

-Intern Ash Turner

This week, the interns were tasked with reflecting on the value of neutrality in museums. After reading Gretchen Jennings sum up her thoughts on what the word “neutrality” really means for museums, I feel that the biggest problem the idea “neutrality” has is that the word itself is out of date and vague.

Besides the fact that full neutrality is not completely attainable, neutrality even means something different for each museum and exhibit. As Gretchen Jennings stated, “…neutrality on some topics is offensive in itself.” This quote stuck with me, especially because we’re interning at a Jewish museum. If the Jewish Museum of Maryland took a “neutral” stance on the Holocaust in their exhibits and didn’t show any empathy for Holocaust survivors, or even if they showed both sides, the nazis and their victims, as equal, then it would probably be offensive. But if a museum of natural history took a neutral approach to an exhibition about insects, it probably wouldn’t be that offensive. Different subjects and collections require different approaches to the content. A blanket term like “neutral” doesn’t really work for the wide variety of museums that exist.

I’ve also heard the JMM talk about “upstanders” when speaking about those who intervened to help during the Holocaust, as opposed to those who watched “neutrally” and were “bystanders.” If museums are neutral, then they are not being an upstanding source of authority for those wishing to learn from them. If they are bystanding and letting the current and future issues that challenge our society pass by, then they are not helping others to learn from past mistakes and apply knowledge to create positive change. If museums stand up and shift their focus to “effectiveness and inclusion,” like the Eastern State Penitentiary (and their article which sparked this whole conversation about museum neutrality), then museums can help create positive change.

I think the main goal of a museum should be not to just to present neutral information, but to create an experience and make viewers question, not just look on neutrally. And for that, museums can’t be completely neutral in their choices and actions. Experience design has been a new focus in the museum community for a reason.

Maybe the standards of museums should be expanded to be “accurate, balanced, and questioning” instead of neutral. Or “effective and inclusive” like the Eastern State Penitentiary. If museums aren’t questioning their own content, they won’t progress. If museums focus on conclusions, on facts and history that has neatly tied up ends, then audiences don’t walk away with anything deep from the experience. What is there to think about, to take away when everything has been said?

Ash chose “Beyond Neutrality”by Sean Kelley as their third article.