More Than An Outfit

A blog post by Director of Collections and Exhibits Joanna Church. To read more posts by Joanna click HERE.

As we wind down our Fashion Statement and Stitching History From the Holocaust exhibits (both closing this coming Sunday, September 15!), it occurred to me that while I wrote many (many) words about the clothing and photographs on display in Fashion, both in the show and for the online extras, I never actually pulled together a blog post. Let’s remedy that!

Contemporary looks at the style choices and expression of artists like Billie Eilish and Lizzo and recent retrospective studies of the fashion of icons such as Ella Fitzgerald and Elton John, help to remind us that, celebrities or not, our clothes make a statement – both intentional and unintentional. What we choose to wear – to work, to school, to shul, to the grocery store, walking the dog – makes an impression on those around us; sometimes it’s the impression we’re hoping to make, sometimes not. That stylish outfit, expensive coat, or band t-shirt says “you’re one of us” to some people, but says “what were you thinking?” to others. In an ideal world, how an outfit makes YOU feel would be paramount – but after all, people are judgey… and that outfit may end up in a museum someday, and there’ll be a whole new set of judgements and appraisals made. One of my goals in Fashion Statement was to encourage visitors to think critically, but also empathetically, about the choices made by others and themselves: what stories do our clothes tell the world?

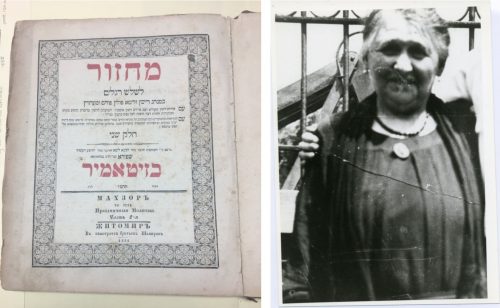

Ida (Chaya) Leikseich Berman (1877-1954) emigrated from Russia with her husband and newborn daughter, landing in Baltimore on July 5, 1900. In 1910 the family – three more children were born in the US – lived on Eden Street, while husband Michael found work as a “street peddler.” By 1920 they had managed to save enough to purchase a building at 125 N. Front Street (near the old Shot Tower, just north of Jonestown), where they ran a second-hand shop. They attended Shomrei Mishmeres, an Orthodox congregation, in the old Lloyd Street Synagogue.

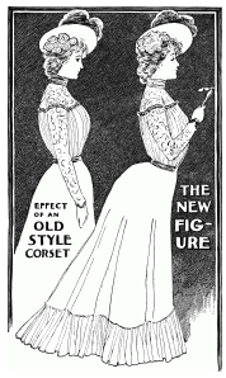

Ida acquired this Edwardian “occasion” gown, made of silk georgette and crepe and embellished with beads and sequins, from an unknown seamstress; it’s possible that she made it herself, though there were plenty of sources for both materials and talent in East Baltimore at the time. It’s well-made, with a complicated top; hand-beading (the sequins may have been pre-strung); a lined and belted top, and a double, flounced, trained skirt. The S-bend silhouette that this dress was designed for was achieved through a blousy top, trained skirt, and (almost certainly) judicious corsetry.

This look was extremely fashionable for the middle of this decade, which could show us that Ida was up to date… though it is possible that the dress itself dates from later in the decade, and she was in fact a few years behind the fashions. Without knowing the particular ‘occasion’ for which it was worn, it’s hard to know if the maker and wearer were of-the-moment, or a little behind the times.

The exuberant sequins on the bodice look modern, but other examples of sequined gowns from this era can be found. Nonetheless, this isn’t necessarily a look or style that we might, today, expect to see on an Orthodox woman; but perhaps Ida – like many of her fellow recent immigrants – enjoyed the newly-available opportunity to embrace the highs of American fashion. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries there was a certain amount of head-shaking and even mockery (including from members of the group themselves, like novelist Anzia Yezierska) of recent immigrants ‘trying too hard’ to emulate the upper classes, or simply being too ignorant to understand what established, mainstream Americans deemed “good taste;” it was feared they were doing themselves a disservice, locking themselves into greenhorn or pitiable status. But today some scholars are hoping to return some agency to these people by showing that many immigrants knew exactly what they were doing when they chose elaborately decorated, expensive, or ‘flashy’ clothing, whether because they were purposefully enjoying a newly-available abundance, indulging in personal tastes unreachable in their previous circumstances, or deliberately setting themselves apart as a sub-group, akin to more recent subculture attire like zoot suits, or punk gear.

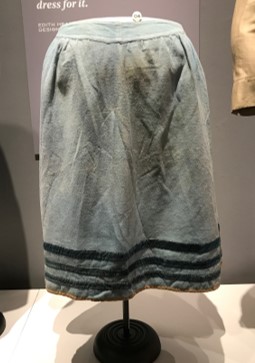

Rebecca Harris Siegel (1869-1934) brought this skirt with her when she, her husband Harry, and at least three small children emigrated to Baltimore from Russia in 1901. They settled in East Baltimore, where census records show that her husband worked in local shops, including a retail confectioner’s in 1910, and as a foreman in an overall factory in 1920. The family stayed in East Baltimore until the early 1930s, when Rebecca, now widowed, moved to lower Park Heights.

Though practical, this flannel skirt is not without a certain amount of style. The material and construction are good quality, and it features three decorative bands of a contrasting velvet trim along the bottom hem. The family thinks this skirt may have been what she was wearing when her ship docked in Baltimore. Without her own testimony, we don’t know if that’s the case – whether she told this to her children, or if it became a story they told themselves over time.

The drawstring at the waist suggests that Rebecca adapted it to wear during one or more of her eight pregnancies (including at least two children born in the US). The many mends and repairs, as well as the overall use wear, show that she wore and washed it frequently, and took good care of it. (And yes, to those visitors who wondered aloud why it was still creased, we tried very hard – within the allowable boundaries of textile preservation – to make it look its best … but this skirt has been through the literal wringer countless times, and it is what it is.) Though a remnant of the “old world,” it was appropriate for a trip to the market or other everyday activities in her new life in Baltimore, when worn with a suitable blouse and coat.

So much for the garments individually. What do these two pieces, when compared, tell us?

They have many elements in common, despite their completely different style and purpose:

>Both were owned and worn by immigrants who arrived (with husband and kids) around 1900, and settled in East Baltimore – in fact both families were living on Front Street in 1910 (Ida at #125, Rebecca at #326). Both women belonged to Orthodox congregations; indications are that Ida belonged to Shomrei Mishmeres, and Rebecca to Anshe Niesen (a Lubavitch congregation, where she’s buried).

>Both garments were carefully saved, and later donated to the museum, by the original owners’ families, who provided us with a little bit of history … but not that much.

>We can learn a lot about these two women today, simply by looking at the materials, use wear, and evidence of care and manufacture.

Another element in common is that both items can lead us into the tempting trap of using a single garment to tell a person’s entire life story. Yes, these pieces can give us some hints, but – especially when what we have, other than physical evidence, is only a few tantalizing details (it was an “occasion dress,” “we think she wore this on the boat”) that seem so helpful at first glance, but in the end are unprovable – those stories we extrapolate are far from representative of each woman’s whole life (and even her whole wardrobe). In particular, we need to avoid using the stark contrast between the dress and the skirt to convey to modern visitors that “Ida was fashionable, and Rebecca wasn’t.”

(Speaking personally, it’s also all too easy to make up increasingly elaborate stories about the people who wore the clothes in our collection … but by sticking as close to the evidence of the textile itself as possible, I can avoid getting too far into the “she loooved flashy clothes!” weeds.)

At the same time, while having only a few pieces of evidence can be limiting or reductive when telling the individual stories of the owners, having both items of clothing helps us to tell a fuller story of immigrant women as a group, going beyond the stock images of recent immigrants fresh off the boat, working in sweatshops, or posed in a family portrait. There are times – whole lifetimes! – that fall in between those photo-worthy moments. It’s important to use all the available evidence to create a more accurate representation of life in East Baltimore in the early 20th century.