Processions, Debates and Curbstone Encounters

The Struggle over Kosher Meat in Baltimore, 1897 – 1918

Article by Avi Y. Decter. Originally published in Generations 2011 – 2012: Jewish Foodways.

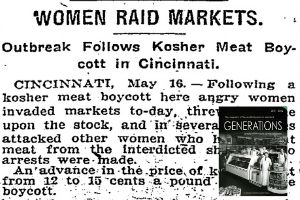

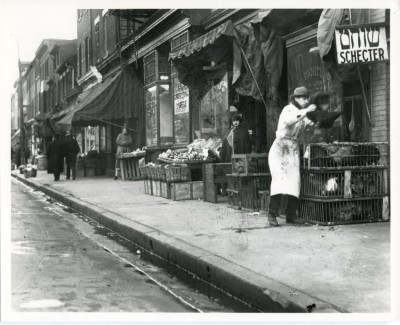

On March 24, 1910, Rebecca Cohen of 221 South Eden Street in East Baltimore was arrested by a City patrolman. Her offense? Mrs. Cohen had seized a package of kosher meat from delivery boy Louis Miller and hurled it into the street. This was not an isolated incident, but part of an effort by Jewish housewives in East Baltimore to roll back a steep and sudden rise in the price of kosher meat. Within days, the Baltimore Sun and other newspapers were reporting that Jewish Baltimore, then a mostly immigrant community residing east of the Jones Falls, was engulfed in a “Kosher Meat War.”[1]

Public meetings, boycotts, confrontations, and arrests punctuated the housewives’ effort to force a reduction in price. As the Baltimore News reported: “Similar incidents are happening every minute or so in the anti-meat district with the result that it is not safe to carry a bundle of any kind unless there is sufficient of the contents showing to satisfy the boycotters that it is not meat.”[2]

The boycott of 1910 was one dramatic episode in a twenty-year struggle over kosher meat that engaged meat wholesalers, retail butchers, shochets (ritual slaughterers), the Orthodox rabbinate, and thousands of ordinary Jews, especially in East Baltimore. In the first decades of the twentieth century, conflict over kosher meat was a familiar topic. Today, that contestation is little remembered and poorly documented. However, sufficient evidence survives to give us access to the trajectory and meaning of the protracted struggle over kosher meat. Here is that story.

Part I: Making Kosher Meat

The rules of kashrut extend back into biblical times, though modified and elaborated over the centuries by both prescription and practice. Kashrut includes rules that govern which animals may be eaten, how they are to be slaughtered, how their meat is to be prepared, and under what circumstances the meat may be eaten.[3]

One rule in particular – that kosher meat must be eating within three days of slaughter – had a direct bearing on the marketing and politics of kosher meat in Baltimore. The rabbis, shochets, and butchers who were producing, certifying, and selling locally slaughtered meat were competing with butchers who were importing kosher meat shipped from Chicago and other centers of the meat packing industry. The former argued that imported meat took too long to travel to Baltimore, making the meat treyfe (unfit), while the latter insisted upon its fitness.

The practice of ritual slaughter (known as shechita) is highly technical. In addition to killing the animal in a precisely defined way, the shochet is also responsible for examining an animal to determine if it is healthy and without proscribed blemish. To carry out his duties, the shochet must be rigorously trained and certified by an appropriate rabbinic authority. But who rabbinic authority is sometimes an open or contentious question.[4]

Continue to Part II: The Issue of Rabbinic Authority

Notes:

[1] “Boycott on Kosher Meat,” Baltimore Sun, 25 March 1910, p. 5.

[2] “Another Arrest in Kosher Meat War.” Baltimore News, 24 March 1910.

[3] David Kraemer, Jewish Eating and Identity Through the Ages (New York: Routledge, 2007).

[4] “’Kosher’ or ‘Trepha,’” Baltimore Sun, 2 April 1897, p. 10. “Scientific Slaughter,” Baltimore Sun, 3 April 1897, p. 10. “Mosaic Butchering,” Baltimore Sun, 6 April 1897, p. 10.