An American in Palestine 4

Mendes I. Cohen Tours the Holy Land Part IV: The Holy City

Written by Dr. Deb Weiner. Originally published in Generations 2007-2008: Maryland and Israel.

Cohen passed through the Jerusalem city gate in the late afternoon, settled into his lodgings at the Convent of St. Salvador, paid a quick visit to the priest in charge, and immediately set off “in search of the Synagogue,” hoping to arrive in time for services. Plunging through the old city, through narrow streets and teeming bazaars, he suddenly found himself swept along with a crowd of pilgrims into the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It was one of Christianity’s holiest sites, “within the walls of which Christ had been Crucified – washed – buried and almost a hundred other things to each of which there is an altar.” Entering a small, stuffy, and overcrowded chamber, “I thus imagined myself within the very tomb of him whom the Gentiles seek.” He hastened out, and “going through the bazaars asked several persons as well as I could make them understand where the Synagogues were.”[i]

Finally someone took him to the “Tyche shool,” or Ashkenazi synagogue, where he asked for Rabbi Mendel, whose name some American missionaries had previously given him. The rabbi invited him for supper after the service. Cohen found him to be “a man about 45 years of age having a young wife not homely. He wore a beard and his headdress was a fur cap which many [of the congregants] wore being pilgrims from Russia, Prussia, Poland, etc.” The following morning in shul they honored Cohen by giving him “one of the high places” and calling him up for the blessing (which, as previously mentioned, he momentarily bungled).[ii]

The Jewish population was divided into two “different sects” that “live in friendly intercourse” with each other, Cohen wrote. “The largest are the Spanish and Portuguese Nusach, the smaller the Tych or Ska-nar-zim, each having their own head or Grand Rabbi to which the Jews of all parts seek for knowledge.”[iii] During his two sojourns in the city he would get to know both groups. He took a keen interest in the lifestyles of his coreligionists and his reports offer a rare glimpse of the Jews of Palestine from the point of view of a western Jew, few of whom had traveled to the region. In fact their visits were so rare that he saw fit to mention that “A year or two ago there were two of our people here from London – a Mr. Sampson and Mr. and Mrs. Montefiore.”[iv] Undoubtedly this was Sir Moses Montefiore, whose life-changing 1827 visit to Jerusalem led him to become the great Jewish communal leader of the 19th century. Palestine would not have this effect on Mendes Cohen. His letters reveal a person who was able to observe sympathetically, but with a fair amount of American-style skepticism, the situation of Jews in the Holy Land.

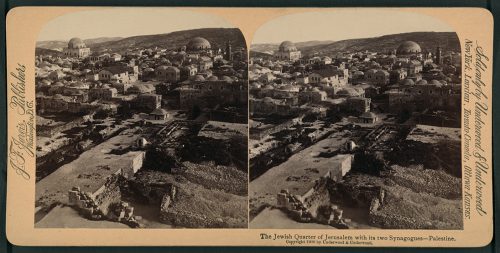

Cohen placed his description of the Jewish community in the larger context of Jerusalem. The city, he wrote, “contains about 12,000 inhabitants of whom about 4,000 are Jews – the rest Turks, Arabs, Greeks, Armenians, etc. and a few Franks (Europeans).” In addition, the city’s ranks swelled with pilgrims of all sorts. “They are all of the poor of the land from whence they come, ignorant and destitute of education bestowing their little means on the numerous Turks who take any opportunity to fleece them. . . . Misery, poverty, lameness and blindness are visible at any step made through the streets of this once great city.”[v]

The Jews, like everyone else, suffered at the hands of the “rapacious Turks” who governed Jerusalem. “The Jews here are generally poor, they also have to pay a certain sum each year to the Turkish Governor,” he noted. The few Jewish families of means were forced to conceal their wealth, lest the Turks “make heavy exactions from the Congregation.” And the synagogues were taxed enough already. “The whole appearance of these synagogues is that of poverty as they are not allowed to build or add to their buildings without paying a large sum to the Turks.”[vi]

Cohen’s American sensibilities were greatly offended by this situation, and he made his views known to his hosts. But “it is in vain that I reason with them,” he declared. “America is the land of milk and honey where each may sit under his own vine and fig tree and none to make them afraid. But the Rabbis have scripture too much at their finger ends and think they are bound to hold on to what once belonged to them and which is now usurped by the Turks.”[vii]

The synagogues may have been poor, but they were rich in Torah scrolls. “The Grand Synagogue of the Spanish & Portuguese Jews is divided into 4 compartments each being a synagogue within itself,” Cohen described. “These 4 Synagogues contain from 100 to 150 Safers or Rolls of the Laws of Moses and several with the Prophets. . . . The Rolls have been presented from time to time by individuals to be kept in the sanctuary – the average price from 50 to 100 dollars according to size, these Rolls are never sent to other places being the gift of pious donors.” The four interconnected shuls in the “Portuguese” synagogue seated between 120 and 300 persons each, much larger and more impressive than the Ashkenazi synagogue—understandable, since the Ashkenazi population was both much smaller (numbering only “300 souls”) and of more recent origin.[viii]

Cohen’s first visit to the Portuguese synagogue occurred on the Sabbath. “There were assembled in all the four shules several hundred of the nation and a great many females in the window galleries. . . . They all wore a white covering over their heads.” He found that “the women are as regular in attendance as the men . . . They are very devout and without participating in the ceremonies practically part of the congregation. They go through all the exercises.” On his return trip in September, he spent Rosh Hashanah there. “I had several honors – was called up as Cohen both days – one day in the shool with the Grand Rabbi.”[ix]

In between sightseeing at Jerusalem’s churches and bazaars and meeting with the local Governor (who served him “pipes and coffee” and introduced him to several Arab “chiefs”), Cohen made time to visit with members of the Portuguese shul and to record his impressions with the dispassion of an anthropologist. He does not indicate how he communicated with his hosts, though he does mention encountering “one by the name of Isaac the son of Solomon who could speak Italian,” and perhaps helped translate. “I found and is generally the case three to four families within the walls of [one] house living together. The withal for living is very scarce here. . . . House rent is cheap. Though you must not suppose they are anything like those we occupy in America. The whole system is different and cannot be easily described.”[x]

He went into considerable detail on relations between the sexes. “I have seen very few single young girls. They marry when twelve or thirteen years of age. The boys marry at about the same age. The whole is arranged by the parents who have to continue to take care of the youngsters. . . . The Jewesses do not cover their faces as the Christian and Turkish females – when they go out they wear a handkerchief around their forehead and down each side of their ears. . . . I was accompanied to the house of a young lady to pay my respects on the birth of a son now two days of age. As the parlors are made into bed rooms when bed-time arrives, we were ushered into her presence. The parents, females were at the bed side. The lady is 14 years of age. . . . Was told by the Chief Rabbi of the Sephardim that a Jew may have more than one wife and there are now some in Jerusalem having two and three wives.”[xi]

Continue to Part V: From the River Jordan to the Sinai Desert

i] Ibid.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Letter to Judith Cohen, September 28, 1832.

[iv] Letter to Judith Cohen, March 19.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Letters to Judith Cohen, September 28, March 19.

[vii] Letter to Judith Cohen, March 19.

[viii] Letter to Judith Cohen, September 28.

[ix] Letters to Judith Cohen, March 24, September 27.

[x] Letter to Judith Cohen, March 24. Cohen seemed to have no problem talking to people wherever he went on his travels, though how he did so remains a bit of a mystery. He clearly knew several languages and possibly some Arabic, the lingua franca of the Middle East.

[xi] Letters to Judith Cohen, March 24, September 27.