Processions, Debates and Curbstone Encounters Part VIII

Article by Avi Y. Decter. Originally published in Generations 2011 – 2012: Jewish Foodways.

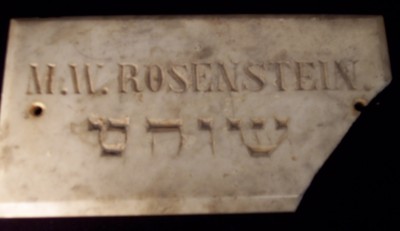

The boycott of 1910 was one dramatic episode in a twenty-year struggle over kosher meat that engaged meat wholesalers, retail butchers, shochets (ritual slaughterers), the Orthodox rabbinate, and thousands of ordinary Jews, especially in East Baltimore. In the first decades of the twentieth century, conflict over kosher meat was a familiar topic. Today, that contestation is little remembered and poorly documented. However, sufficient evidence survives to give us access to the trajectory and meaning of the protracted struggle over kosher meat. Here is that story.

Part VIII: Memory and Meaning

Missed the beginning? Start here.

A drama with so many scenes and so many actors lends itself to multiple interpretations. At its simplest level, the story is that of economic self-interest. The shochets were trying to make a decent living and to this end demanded increased compensation for their work while restricting access to the profession and resisting the importation of dressed meat from the Western packing houses. The local kosher meat wholesalers were caught between the shochets and the retailers – and under constant pressure from competitively priced Western beef.

The retail butchers and shopkeepers were under pressure from the local Orthodox rabbinate to market locally slaughtered beef and experiencing increased costs; when they tried to pass these increases along to their customers, the housewives of Baltimore – supported by unions and other local organizations – resisted fiercely, producing a series of boycotts, demonstrations, and occasional incidents of violence. The superimposition of the U.S. Food Administration and the constraints of a wartime economy exacerbated exhibiting marketing pressures, even after nearly twenty years of sustained struggle.

But economic self-interest offers only one perspective on this long and tangled tale. Ideology also played a key role. The Orthodox rabbinate, living in an American Jewish community in which their traditional authority was not well-established and concerned about loss of authority under conditions of Americanization, used their supervision of kosher meat making as a way to assert their leadership role in the community (as well as bolster their incomes). The rabbis’ stance on close supervision was also a key stimulus to the emergence of a distinctive Orthodoxy in Baltimore and to its institutionalization in the Federation of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations.

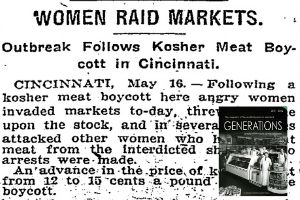

At the same time, the kosher meat wars within the Jewish community were also an expression of a very American struggle occurring during this period. During the Progressive Era, as it has veen termed, there were repeated efforts – local and national – to break up monopolies, restrain unfair practices, and reduce the power of large corporate enterprises. One of the characteristic forms of the trust-busting impulse, at both the local and national levels, was food strikes and boycotts. Consumer strikes against producers and marketers of milk, eggs, bread, and other staples were common in this period.[1] The Progressive impulse to restrain the power of the trusts influenced Jewish communities around the country, as shown by kosher meat strikes in New York (1902, 1910), Boston (1902), Philadelphia (1907), Chicago (1910), St. Louis (1910), and Cincinnati (1917), among many other cities.[2]

Historians have interpreted food protests in a number of ways. One approach sees food strikes as an expression of a traditional, pre-industrial mentality. In a feudal economy, bread was sold at a “just price” as part of the communal moral ethos; as the modern market economy emerged and superseded the traditional peasant economy, food riots became a way for people to protest what they believed were efforts to deprive them of food to which they had a moral and political right. A specifically Jewish aspect of the urge for a “fair price” may echo a lingering resentment of the korobke (meat tax) that was levied on kosher meat in Central and Eastern European communities and that constitute a primary source of communal income.[3]

A second understanding of food strikes focuses on the roles of women. During the nineteenth century, food riots began to take on a female persona. Paula Human, for instance, views boycotting women as expressing “their power as consumers and domestic manager” and evidencing “a modern and sophisticated political mentality.” The militancy of Baltimore’s Jewish women reflects their participation in labor struggles and a general environment of labor militancy among the Jewish working classes. Even their language is similar to the language of labor activitists. And, around this time, women were increasingly taking leadership roles in garment industry organizing because they constituted a growing percentage of the workforce. The kosher meat strikes underline female consciousness and leadership, not to mention their competence in networking and in organizing mass meetings, demonstrations, and boycotts.[4]

Still a third perspective focuses on the cultural meanings of the food themselves. For Jewish women, “the rituals of preparing kosher foods played a crucial role in [their] religious and cultural self-definition…Women bought and served traditional foods not only out of mere habit, but also because those foods expressed their commitment to a religious life.”[5] The long struggle over kosher meat, then, reflects the symbolic power of food in the forging of personal and communal identity, the process of cultural adaptation, and the distribution of authority and power in Jewish Baltimore a century ago.

~The End~

Notes:

[1] See, for example, “Progressive Era,” at Wikipedia.

[2] Local reportage on food strikes in other cities include: “Many Quit Buying Meat [New York City],” Baltimore Sun, 19 May, 1902, p. 2. “Meat Riots in Boston” Baltimore Sun, 23 May 1902, p. 8. “No Kosher Meat for Sale [Philadelphia],” Baltimore Sun, 27 July 1907, p. 12. “Meat Boycott Spreads [Milwaufee, Cleveland, et al.],” Baltimore Sun, 22 January 1910, p. 1. “Meat Boycotters Aroused [Chicago],” Baltimore Sun, 4 April 1910, p. 14. “Women Win By Boycott [Pittsburg],” Baltimore Sun, 11 May 1916, p. 1. “Egg Boycott Started [New York],” Baltimore Sun, 28 November 1916, p. 1.

[3] Amy Bentley, “Bread, Meat, and Rice: Exploring Cultural Elements of Food Protests and Riots,” Oregon State University, 2000; updated 23 May 2012, pp. 3f.

[4] Paula Hyman, “Immigrant Women and Consumer Protest: The New York City Meat Boycott of 1902,” in Jonathan Sarna, ed. The American Jewish Experience, 2nd ed. (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1997), pp. 153-164.

[5] Dana Frank, “Housewives, Socialists, and the Politics of Food: The 1917 New York Cost-of-Living Protests,” Feminist Studies, 11, 2 (Summer 1985): 256 cited in Amy Bentley, “Bread, Meat, and Rice, “ p. 5.