Portrait of Fredericka Herstein; or, an afternoon down the rabbit-hole of historical research

A blog post by Collections Manager Joanna Church. To read more posts by Joanna click HERE.

Here at the JMM, some of our portrait collection is hung on move-able racks in one of our storage rooms, meaning there are certain faces that greet you when you access the archives.

Last week, thanks to the position of the racks, one of our 19th century ladies caught my eye several times; when, coincidentally, I came across her catalog record, I decided to delve into a little research on her history.

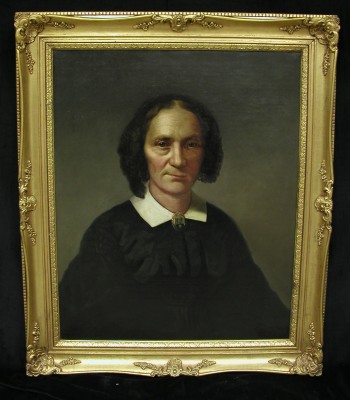

This is Fredericka (also known as Frädche) Wiesenfeld Herstein (1797-1873), painted by an unknown artist. Family information tells us that she was born and raised in Germany; her first husband, Joseph Wiesenfeld, died around 1820; by 1824, she had married Meyer Herstein. Immigration records show that in 1854 Meyer and Friedrike (Fredericka) Herstein, along with their daughter Bertha, traveled from Bremen to New York on the Hansa. Shortly thereafter they made their way to Baltimore, where their son Nathan may have already been established as a clothing manufacturer. Meyer died around 1858, and the 1860 census shows Fredericka living in the Baltimore household of Nathan and his young family. She died in 1873 and is buried in the Oheb Shalom Cemetery, Baltimore, as Fradche Herstein, “our beloved mother.”

At first glance the painting itself is not terribly informative. It is unsigned, with no inscriptions to tell us the date, sitter’s name, or place. On the other hand, it is in great condition and in a relatively modern frame, telling us that over the years Fredericka’s portrait was well cared for as a treasured family heirloom. Looking more closely, the image gives a few other clues to her story – not many, but enough to start the speculation engines.

The donor suggested this was painted in the 1840s, and the fashion – a gown with dropped shoulders and wide sleeves, and the sitter’s center-parted ringlets – could support that. However, a few factors (including the high, straight waistline) make me think it may be from the late 1850s, when those details would still apply, but would make up a slightly different silhouette if we were seeing her at full length. (Here are two summaries of mid-19th century fashions, from the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, if you’re interested.)

As much fun (seriously!) as it is to parse out the various details of a subject’s attire, when dating old photos and paintings it is important to remember that just because the fashion prints for a particular year are showing haute couture, not everyone adopted those trends immediately (or ever). What was hot in New York or Paris might not make it to the seamstresses and tastemakers of far-flung cities for quite some time. And who among us hasn’t clung to a comfortable and/or flattering garment, in defiance of shifting hemlines and changing color palettes? Fashion and clothing style are good clues, but they don’t always provide the definitive answer we’re looking for.

Speaking of color palettes, that’s another telling element of this painting: the black gown and black lace cap indicate that she’s likely dressed in mourning, at least to some degree. The brooch pinned to the center of her collar features the image of a man, currently unidentified and perhaps the object of her grief. While it could be a son, or another recently deceased relative, or even her first husband Joseph Wiesenfeld (who died around 1820), I’m inclined to think it may be her second husband Meyer Herstein, who died in 1858. If so, then this was painted in the United States – possibly even in Baltimore – in the late 1850s, when she was herself in her early 60s, which I think matches her apparent age and fashion choices.

…And this is the tipping point of the slippery slope that should be avoided, or at least approached with caution, by imaginative Collections Managers. I can (and have!) come up with lots of theories and scenarios for the subjects of this and other portraits, but while entertaining, they shouldn’t be taken as anything other than speculation. In reality, I know that my reasoning is a trifle circular (1850s makes sense for the dress, so it must be Meyer’s brooch, so it must be the 1850s), and that there’s lots more research to be done before we can suggest with more conviction when this was painted, and under what circumstances. But that’s the fun of historical research! There’s always something else to look up, and more stories to uncover.