The Lloyd Street Synagogue’s Chandeliers

A blog post by Director of Collections and Exhibits Joanna Church. To read more posts by Joanna click HERE.

When Baltimore Hebrew Congregation expanded their synagogue in 1860, pushing the east wall 30 feet out, they kept track of their expenses – including $390 spent on a “chandelier & gas fixture.” (Fun fact: adjusting for inflation, that would be about $11,245 today.) During the restoration of the building just over a century later, researchers at the Jewish Historical Society of Maryland (now the JMM) found those records in the BHC archives, looked up at the two beautiful antique chandeliers that came with the building, and concluded:

The two massive crystal chandeliers which hang from the ceiling of the restored Lloyd Street Synagogue have been rather positively identified as these which were installed at the time of the 1860 enlargement of the building…

-Jewish Historical Society of Maryland press release, 1964

The historians at the JHSM soon realized the error, however, and began to investigate a more accurate version of the LSS chandeliers’ history. For one thing, in the 1960s there were still several early members of Shomrei Mishmeres at hand, at least one of whom remembered when and how the chandeliers were acquired. For another, this style of light fixture likely wasn’t manufactured until the 1870s, making it difficult to have installed them in 1860. Over the decades, we’ve uncovered more and more about these pieces, but it was a recent coincidental discovery that brought them back to my attention, just in time for our celebration of the synagogue’s 175th anniversary.

The Lloyd Street Synagogue, taken September 2020

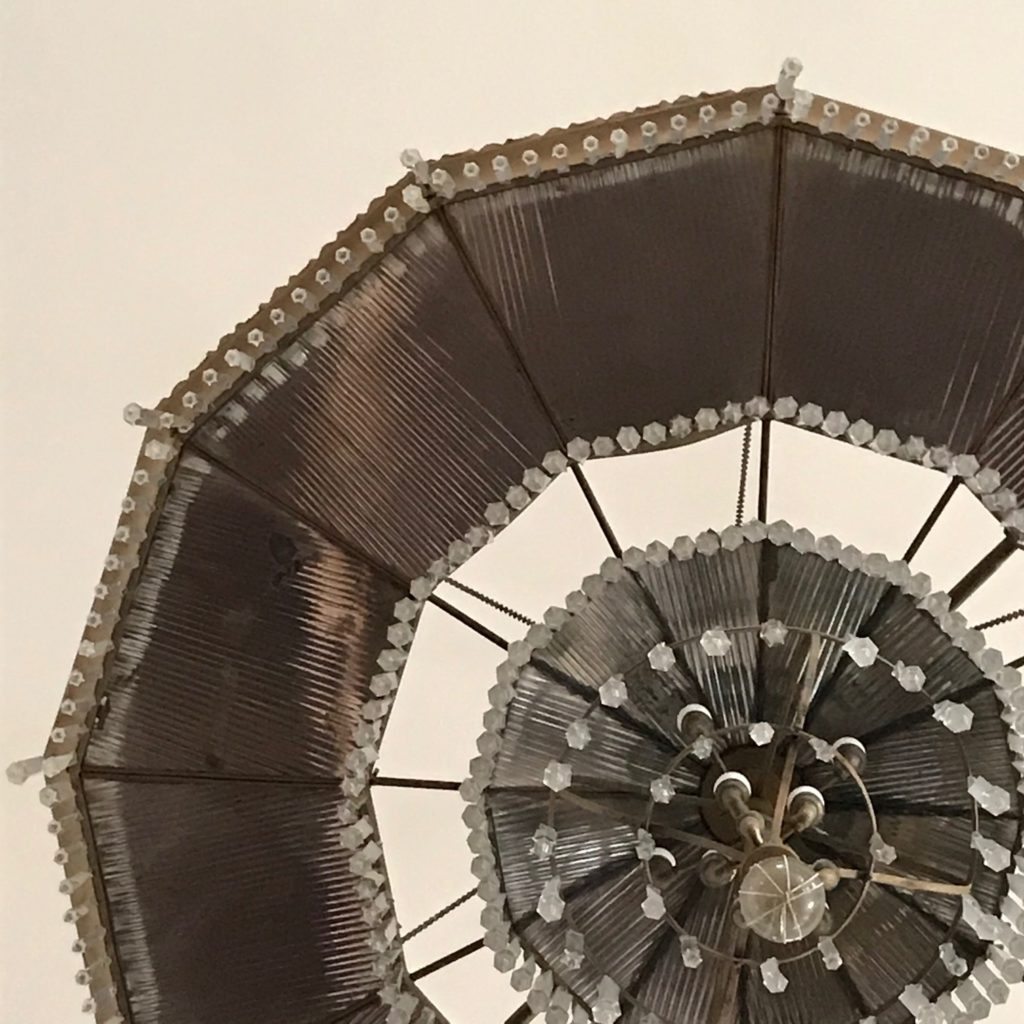

I drive past Old Otterbein United Methodist Church every morning on my way to work, but I’ve never been inside. Happily for me, Wendy Davis, our Volunteer Coordinator, took a tour (pre-pandemic), and noticed that not only do they have a similar chandelier, they also know who made them: the Bailey Reflector Company. When Wendy shared that with me, I started down a rabbit hole of research, compiling existing and new (to me, anyway) info about our particular chandeliers, and the company that made them.

*****

Cover of a Bailey Reflector Company pamphlet, 1881. From the collections of the Corning Museum of Glass.

The Bailey Reflector Company, Pittsburgh, PA, appears to have been founded in the 1870s; patents, advertisements, and a few extant examples in museum collections date to the 1870s-80s. The advantage to a house of worship that chose a compound reflecting chandelier – besides the impressive aesthetic, particularly evident in the more Gothic designs like ours – was the use of reflective mirrors carefully placed and angled so as to send light into a broader space, especially in a room with a high ceiling. As the text in the above brochure touts, earlier and inferior reflecting lamps

concentrated the rays of light in a limited space, immediately under the fixture… [so] when used in churches, halls, &c., they have to be hung too high in order to light the room that the effect has, to a certain extent, been destroyed, and have consequently failed to give satisfaction.

Bailey’s Compound Light Spreading, Silver Plated, Corrugated Glass Reflector, available in gas or oil format, “ornamental, cheap, convenient, and safe,” overcame this issue by adding non-corroding silvered plates, at angles guaranteed to “at least double the light and distribut[e] it in every direction.” Even today, converted into electric, missing a few prisms, and (we know, we know) in need of a thorough cleaning, our chandeliers give proof to Bailey’s claims.

The Lloyd Street Synagogue, taken September 2020

*****

As to how these fixtures ended up in the Lloyd Street Synagogue, the generally accepted story that we tell today is that they were originally in the Second Presbyterian Church across the street, and Shomrei Mishmeres Congregation acquired them in the 1920s when the church was torn down.

A view of the south side of E. Baltimore Street at Lloyd Street, 1909. The two spires of the Second Presbyterian Church are visible; the white building next to it is Talmud Torah. If you walked down the street and turned right just past the church, you’d see the Lloyd Street Synagogue… but unfortunately, the photographer was not kind enough to stand where it could be seen for this photo. Gift of Earl Pruce. JMM 1985.90.14

The Second Presbyterian’s first building at Lloyd and Baltimore Streets was erected around 1803; the second building, a much grander edifice, replaced it on the same site several decades later. In 1884, that building was refurbished, and the Sun reported,

The present church edifice, which was built about 1849, and has been heretofore several times repaired, has never been as handsome as at present…. The interior of the church has been re-frescoed in rich colors, the pews oiled and varnished and the cushions recovered. Two elegant prismatic reflecting chandeliers have been provided, which furnish a pleasant light and add very greatly to the beauty of the interior of the church… the chandeliers [were] furnished by Messrs. C.Y. Davidson & Co [plumbers and gas fitters].

-The Baltimore Sun, November 2, 1884

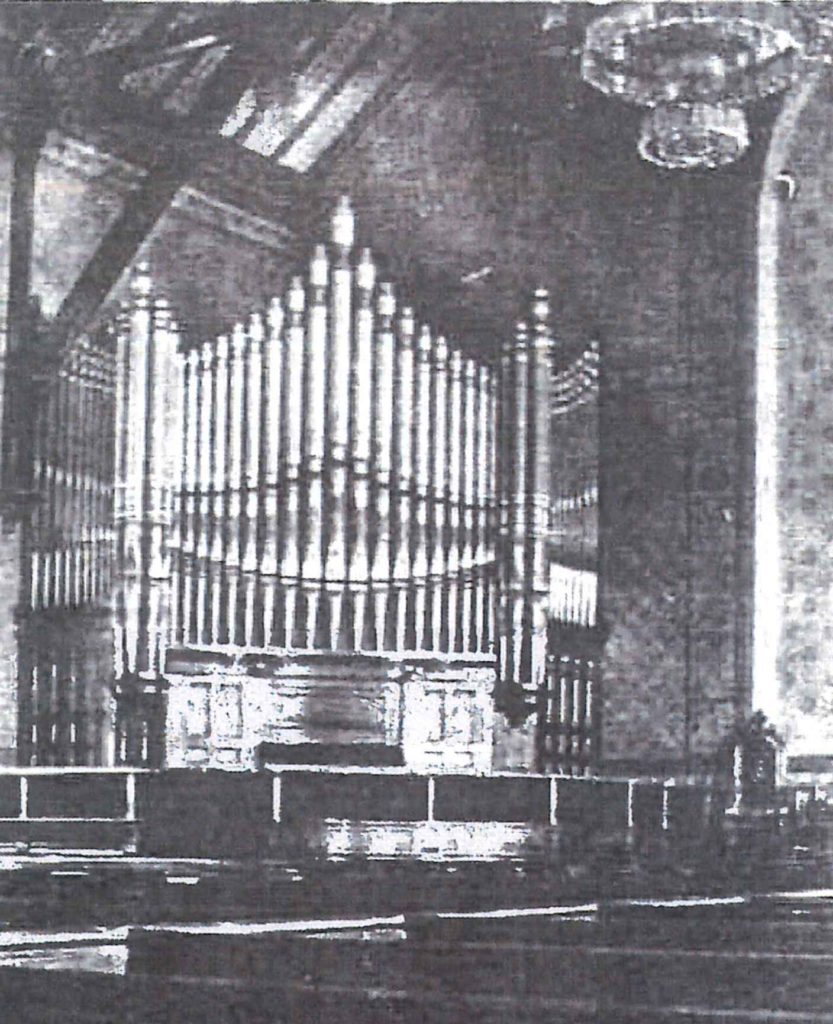

This photo of the interior of the Second Presbyterian Church, circa 1900, is focused on the impressive organ – but the lower edge of one of the “prismatic chandeliers” is visible in the upper right corner. Courtesy of Second Presbyterian Church, Baltimore.

In a story that will be familiar to those who know the histories of so many of Baltimore’s synagogues, the congregation of the Second Presbyterian began moving out of downtown, and the church had to follow them. In 1924, plans were afoot for a new building in Guilford, and the 1852 building was razed. According to the Sun, “the old edifice, with the site, has been acquired by Herman Scheer and Israel Silberstein,” developers who planned to build stores and a recreation center on the site. (I believe it was actually a bank that was built there, though now the site is home to Helping Up Mission.)

The Lloyd Street Synagogue, taken September 2020

In 1979, Gedaliah Cohen (1904-1988) wrote his memories of “the acquisition of the Lloyd Street Synagogue Chandeliers” for our journal, Generations. Mr. Cohen attended Shomrei Mishmeres at the LSS starting in 1920, “the week of [his] arrival in the United States as an immigrant from Russia,” at the age of 16. He began his article by noting that when the “Christians in the area decided to build a church” (it’s not totally clear, but it looks like he means the 1852 building), “the synagogue” (Baltimore Hebrew, presumably) loaned their neighbors the money to complete the building, later turning it into an outright gift.

When the church was being torn down in the 1920s, Mr. Cohen remembered, developer Israel Silberstein “noticed a pointed object sticking out from under the heap of brick and debris of the destroyed church” while walking near the site; he pulled the whole thing out of the pile, realized what it was, “had [them] cleaned and restored to their original beauty,” and offered them to Shomrei.

Once hung, Mr. Cohen recalled, there were immediate concerns from members about the appropriateness of hanging church fixtures in the synagogue. In fact, “the sacred service [at Shomrei] came to a halt and turmoil and chaos took over,” with the majority of congregants vociferously against keeping the (already installed) chandeliers.

But, at the moment of crisis, just when members strove to have the chandeliers removed, Rabbi Schwartz mounted the bimah. Somewhat pale and grieved over the tumultuous uproar, he asked all to take their seats. Then he calmly informed the worshippers that he, and he alone, was responsible for accepting the gracious gift from Mr. Silverstein [sic], being fully aware that the chandeliers came from the church. Rabbi Schwartz next quoted a few rabbinic statements supporting his acceptance to the effect that, whereas no synagogue or any sacramental content of a synagogue should ever become part and parcel of a house of worship of another faith, the opposite is perfectly permissible. It is acceptable to convert a church into a synagogue or for any part of the church to become part of the synagogue.

And so the chandeliers stayed, and are still hanging today. To Mr. Cohen, this was only natural; the Jews of Jonestown had helped the church build and furnish the church with a gift of funds, so it was fitting that some of the fruits (he assumed) of that money should return to benefit the neighboring synagogue.

*****

I love the synagogue’s chandeliers; they are fabulously fancy, for one thing (though this style won’t fit in my house, alas), and their complicated, multi-faith, still-in-question history only adds to their charm. Even so, while I enjoyed discovering more about the Bailey Reflector Company (they built a company town called Reflectorville!) and the connections between the church and synagogue, one of my favorite parts of this research was more simple and straightforward: a brief note by one of my predecessors, attached to a copy of Mr. Cohen’s Generations article, which cautions, “this is just recollections. The information has not been substantiated.”

Memories can fail; assumptions can be incorrect; stories change, and are exaggerated or shortened or refined (or all three) over time. In the 1980s-90s, when JMM researchers interviewed people who had attended Shomrei as children, some did not mention the chandeliers at all, while Morris Weintraub said, “of course the chandeliers I remember first of all.” Sadie Rosenfeld Sacks, daughter of the congregation’s shamas Yehuda Rosenfeld, actively rejected any memory of them when interviewed in 1986, but in 1992 shared the story about them coming from the church – except she told us the congregation wanted to use them, and had to work to convince the rabbi. The photo of the chandelier in the Second Presbyterian Church is a great clue, but I can’t prove that it’s the exact same chandelier. We were totally wrong about the chandeliers’ history in 1964, and it may turn out that we’re still not quite all the way there. Research (one should always make clear) continues.

The Lloyd Street Synagogue, taken September 2020.