Everyday Heroes: Interview Part I

Article by Deborah Rudacille. Rudacille is a freelance writer and Dundalk native. Her book about her hometown Roots of Steel: Boom and Bust in an American Mill Town, was published by Pantheon in 2010. Article originally published in Generations 2009-2010: 50th Anniversary Double Issue: The Search for Social Justice.

Q: Were you both raised in households where there was a strong emphasis on social justice as an aspect of Jewish identity?

Larry: Absolutely. If for no other reason, the period of time when we were growing up. I was born in 1930 so you had the Depression and the tragedy of the Second World War where people were murdered for their religion or their sexual orientation or for whatever reason the Nazis wanted them murdered. I think that ties in to what we did. However when my first wife and I moved to Baltimore in 1958, the recognition of the terrible toll of prejudice, the reality of the situation, took a while to set in. I was living in a cocoon when it came to racial segregation. It just didn’t register. The horror of it didn’t dawn on me until the early 1960s at Social Security. I worked in the policy division. And it was a great big room, larger than this house, and if you walked through that room your eyes told you immediately what was going on. Because you had hundreds of desks with all black faces and all the supervisory enclaves, these little cubicles, all white. Worse than that, the white people who were selected to supervise were frequently not well-qualified. They needed the black employees to orient them to what had to be done.

Q: So for you, it wasn’t until you were an adult, a husband, a father, a worker, that you were first confronted with this injustice.

That’s right.

Q: What about you, Helene, when did you first become aware of injustice?

Helene: In Buffalo, which was a working class town, I had been interested in the trade union movement. I don’t really recall why except it seemed to me an important counterbalance to the power of the business people and the corporations. My father was a small businessman, a realtor, and he had sympathy for the “little guy” as he used to put it, too. But we weren’t activists.

Q: It wasn’t until you came to Baltimore that you became involved in civil rights activism?

Not exactly. One of the first things I was involved in was a march in support of the Brown vs. Board of Education decision while I was still in Buffalo. Somehow I heard that CORE wanted people to demonstrate in favor of this decision and that’s how I first learned of CORE and Bayard Rustin. In Buffalo, some friends of mine, we just got out on the street and handed out leaflets and we went to the black churches in town and we developed a group of people to go down, a couple of buses, to go down to Washington D.C. for the demonstration. That would have been around 1956.

I joined CORE and soon afterwards I married and moved to D.C. for my husband’s job—he was education director for AFSCME [American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees]. There were quite a few Jewish people involved in CORE at that time.

I didn’t know [Bayard Rustin] personally at that time but we were acquaintances. Then later we became friends. Bayard was so instrumental. He had experience with non-violent action and we were a non-violent action group. I had been very interested as a young person in Gandhi and the movement and this is why all this was very compatible but he’d had years of experience of being in violent situations and how to behave to lower the temperature of things and he was passing this knowledge on to this whole group of young people. He was an incredible person. I remember he used to say to me, “Look them in the eye. It’s very hard for someone to hit you when you are looking them right in the eye.”

Q: So you were starting to go to sit-ins to integrate lunch counters?

We were creating the sit-ins, in Washington and in Northern Virginia. And we were supporting the sit-ins that were taking place around the country. Our group, the Nonviolent Action Committee (NAG), was instrumental in desegregating Glen Echo amusement park in Maryland [in Montgomery County, just outside Washington]. That was interesting. We were all arrested at different points for disturbing the peace. That was the next step in my education. Because I heard at least one police person saying things in court that were untrue about our actions, that we were unruly or being disruptive. Well, we were very quiet middle-class blacks and whites just walking and holding signs. They said we were preventing people from crossing the picket lines, but we were not. We were actually being verbally harassed by hoodlum-like people.

In lunch counter situations we were being physically threatened. Some people would come up and yell obscenities and lift things to throw at us. We were protected, not by the police but by the press. The press stood on the opposite side of the counter so they could get pictures, and the minute anybody would try to do anything the reporters would raise their cameras. They were very deliberate about it. They were very sympathetic to the demonstrators.

We were young people and very frightened. But all these experiences sort of unified NAG, an amalgamation of people from CORE and Howard [University] students and some people from the community that had heard of us and joined.

Q: How big was this initial group?

Fifteen to twenty-five people. But people would come and go. When we went to Glen Echo, interestingly enough, there was this cooperative housing and community called Bannockburn in Greenbelt, built during the New Deal, and a lot of the people there were Jewish trade union people. I remember that from the first day we started to demonstrate they came out, a whole group of them, and offered us facilities in their community to take a nap, get some food, or to just hang out in their houses. They would bring food to the picket line, and water. They were very supportive, and that was a big help.

Q: When did you go to Mississippi?

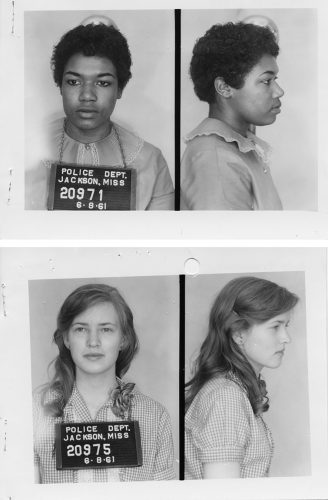

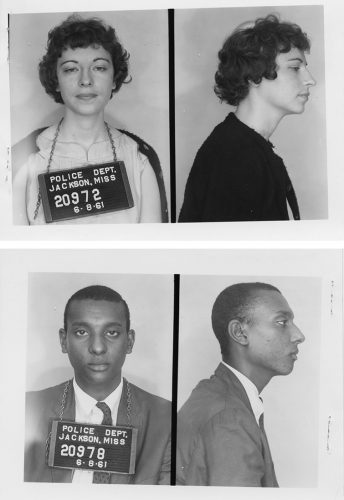

The Freedom Rides started in ‘61. There was a call by CORE to fill the jails with Freedom Riders in Mississippi. There were three people I knew well from NAG that decided to go: Gwendolyn Greene, a young black woman, a Howard University student who would many years later become a Maryland State Senator; and a young white woman named Joan Trumpauer, eighteen years old and this beautiful, beautiful girl. And Stokely Carmichael. I knew him when he was a Howard student. As a matter of fact he stored some of his clothes in my apartment. When we knew we were going to be incarcerated, he gave up his apartment.

The Freedom Rides started from New Orleans. Our group was on a train. The train stopped somewhere in Mississippi. The plan was for Gwendolyn and I to get off at that stop. When we alighted from the train, we were approached by a very poised, well-dressed young black man who said “I’m John Lewis from CORE, and I just want you to know that we are here and will be watching over you.” His demeanor was so reassuring. Of course, he was later to become a Congressman. We were told to have a drink of water from the same “whites only” fountain and sit down on a bench together, which we did. Shortly afterwards the police appeared and arrested us for disturbing the peace. It was a planned action, and everyone knew their role.

Q: So they put you in jail?

Yes, but we were separated. They put us in the county jail, a big room with bars in front, and next to us was another one where they put the black girls, and the guys were somewhere else where we could hear them but we couldn’t see them. This group from California came just before us, so it was very crowded.

I was scared. We really didn’t know what to expect. Joanie, on the other hand, was very calm. I didn’t know many people in this group that we were in jail with and in fact they even put some women in there to spy on us. One woman was there for another reason but she eventually told us that they had said for her to take notes to see if we were being paid, who was paying us, were we communists.

In the middle of the night once, I heard someone call my name, “Helene, Helene.” You couldn’t see the people in the jail cell next to us, you could only hear them. But all of a sudden at the end I saw a hand come out and it was Gwendolyn and she was waving her hand. And I went and clasped it. And we just held hands for dear life. It was such a close moment with Gwendolyn. I never forgot that. Then they transferred us to Parchman Penitentiary.

Q: Why did they transfer you? Was the county jail too crowded?

CORE’s purpose was to fill the jails and to demonstrate to the country the ridiculousness of the whole situation, that for just sitting on a bench or drinking from a fountain, people were put in jail. We could have paid bail and gotten out, but the idea was to stay as long as we could but get out just before forty days because after that, we could not appeal it. We stayed as long as we could. I was there thirty-eight days. People kept coming in, and we really did fill the jails. They had to move us to Parchman because there was no more room in the county jails and the country became aware of it.

Q: What were conditions like at the prison?

The men really suffered. Several were put in isolation. The guys said they were very badly treated but were reluctant to be specific. We were middle class kids and it was hard. They gave us food, very simple food, but without any salt so that people could just about eat it. They would turn off the water in all the cells so you couldn’t flush the toilets. In a closed space the smell became difficult to bear. I remember thinking very clearly about Jewish people being transported in boxcars with no toilet facilities. We were so crowded in the cells that we all had to take turns to lie down to sleep and that also made me think of the boxcars of the Holocaust. The link in my mind was very strong.

Q: The link between what you were experiencing and what Jewish people had experienced during the war?

Yes. And some of the guys who had bad experiences to this day have not totally recovered. It was hard. For some, harder than others.

Continue to Part III of Everyday Heroes