Family Fare Part II

Article by Jennifer Vess. Originally published in Generations 2011 – 2012: Jewish Foodways

Part II: Immigration: “In the United States they would have an opportunity.”[1]

The streets of America may not have been paved with gold at the beginning of the twentieth century, but immigrants flooded into the United States looking for opportunities. A large number of Jewish immigrants chose food as their opportunity. New arrivals could begin modestly and gradually build a business, supporting their families and even giving a boost to others.

Sol Grossfeld a baker from Radom, Poland immigrated to the United States in the 1920s and established the Warsaw Bakery with partner Solomon Hartman. Courtesy of Mrs. Gertrude Grossfeld Katz. JMM 1992.211.1

Immigrants did not often arrive in America with much money, but even so many sought to support themselves rather than relying on employment in someone else’s business. The Lozinsky family, for example, started as small as anyone could. They “would take big baskets to the fish market, buy fish, and bring it back. Then they would stand on the sidewalk and sell the fish.”[2] Others sold out of carts or stalls on the street or out of rooms in their homes.

These small shops supported more than just the immigrants who started them. The benefits often spilled out to others in the immigrant Jewish community. Once settled in America, men and women helped to bring over siblings and cousins and other extended family, sometimes giving them jobs until the new arrivals could move out on their own. As Milton Schwartz of Crystal’s bakery explained, “Everybody that my parents would bring over from Europe, they gave them a job in the bakery. I had several cousins working there. Until they got their start in the New World and could go out on their own, they always had a job in our bakery doing something.”[3]

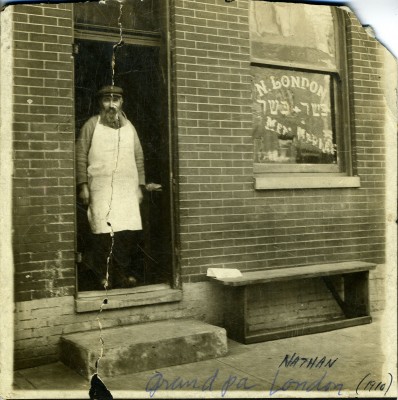

Nathan London, born in Russia, opened a kosher butcher shop on Lombard Street, c. 1900. Courtesy of George London. JMM 2001.109.1

Some of the more successful businesses with large workforces gave jobs to new immigrants who were not relatives, perhaps remembering their own struggles trying to make a living. Gustav Brunn (later the creator of Old Bay and owner of his own large company, Baltimore Spice) worked briefly for Wolf Salganik, the meat processor before striking out on his own.[4] As late as the 1980s, Brunn’s workforce included a large number of recent immigrants from Europe and Asia.

In some cases settled immigrant families offered homes to newcomers. Charles Bluefeld, whose wife later started Bluefeld catering, came to Baltimore without any connections. When he immigrated in 1906 he boarded with the Schreiber family, who ran a meat business (and later a supermarket), though he had no connection to the family and did not work for them. From earning money to providing a home food gave many immigrants a start.

Continue to Part III: Learning the Trade: “Baking was the only trade he knew.”

Notes:

[1] Dora Silber and Kathryn Sollins interview, n.d., OH 123, JMM.

[2] ibid.

[3] Milton Schwartz interview, November 9, 2005, OH 676, JMM.

[4] Louis and Philip Bluefeld, interview, August 6, 1979, OH 75, JMM; Gustav and Ralph Brunn interview, May 7, 1980, OH 112, JMM.