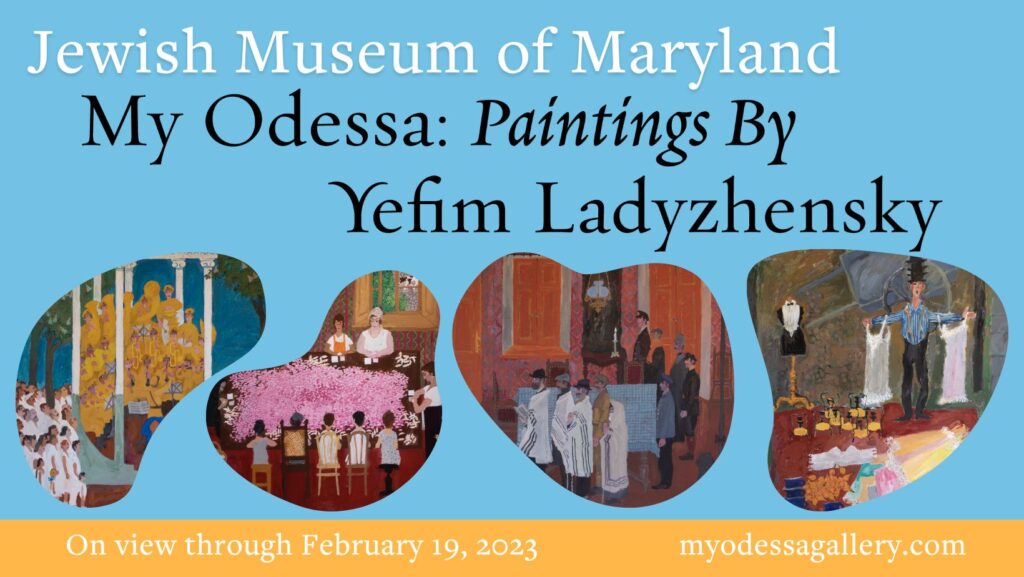

My Odessa: A Conversation with Curator Liora Ostroff

A conversation between JMM Executive Director Sol Davis and JMM Curator-in-Residence Liora Ostroff. Liora is the curator of My Odessa: The Paintings of Yefim Ladyzhensky.

Sol Davis: The JMM deliberately chose to hire you, a painter, to curate this show of paintings. How has your relationship with and practice within the medium of painting informed your curation of this exhibition?

Liora Ostroff: I would never want to study film, because then I don’t think I could sit through a movie without thinking about how it was made. When I look at Ladyzhensky’s paintings, I feel like I am flooded with soap-box commentary about how he handles his brush, develops his palette, and composes his images.

As a painter, it’s easy for me to imagine being in the studio with him: I can hear him muttering about his choice to paint in tempera on cardboard or burlap, as opposed to finer materials, like oil on canvas; I can see him carefully painting over figures, painstakingly remixing a color from earlier on, and dotting the canvas with stones.

Because I am so drawn to his palette, I chose to draw out certain colors for the exhibition that the artist himself favored and named: the creamy imported limestone of his neighborhood; his quiet, earthy greens; his bright blue Odessan sky; and the deep, rich color, close to what he calls “Berlin blue,” of Lanzheron beach’s waters.

Sol Davis: How do you think Ladyzhensky’s art transcends the label of “naïve” or the box “folk art” that it has at times been assigned to, and how does it relate to historical art and modernist trends?

Liora Ostroff: Ladyzhensky was committed to painting sentimental scenes and people at a time when abstraction and formalism were in vogue. Ladyzhensky chose not only to sidestep those trends, but publicly decry them—in a 1979 essay written while living in Israel, he condemns Israeli artists for “neglect[ing] craft,” for being “imitative,” unable to “move away from…the style that influenced them.” He declared, “I do not accept any ‘isms’ – it is very possible that I am outdated, but nothing can be done about it. Formal art has always and everywhere been alien to me.”

Although certain aspects of modernism clearly disgusted him, he did not eschew his technical training and knowledge of art history, both recent and distant. One of his avid collectors, Yevgeny Kalinsky, pointed out to me that in Ladyzhensky’s painting Discounted Goods for Sale, the seller stands in the same position as Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Ladyzhensky’s composition mirrors that image in other ways: a large wheel behind the seller mimics the circle around Vitruvian Man.

I find echoes of art history in many of his images: We Were Wrapping Candies brings to mind various Last Supper images; his use of color in certain paintings—for example, his striking blues in Listening to the Radio for the First Time—remind me of Wassily Kandinsky’s theories about the psychology and emotional resonance of colors. Ladyzhensky’s blues are dreamy and rapturous.

Ladyzhensky created this body of work in the 1960’s and 70’s, but he was anything but naïve about the trends and art movements of his time. He consciously and vociferously rejected them.

Sol Davis: Will you speak about your decision to situate Ladyzhensky’s written stories and fragments of memoir alongside his paintings in this exhibition?

Liora Ostroff: Ladyzhensky’s paintings are bursting with personality and wit, but I found that it took a deeper familiarity with his personal narrative to perceive those things in his images. And when I began this project with only a few scattered comments and excerpts from the artist at hand, I found myself marveling at his insufferable arrogance, and what one writer referred to as his “huge, squirming ego.”

But when I had the chance to read Ladyzhensky’s stories and memoirs, I found him to be an increasingly sympathetic character. I gained a deeper understanding of his feelings of rootlessness and alienation, his moodiness and melancholy, and even his arrogance. His humor winds through every reminiscence and turn of phrase, but many of these stories are punctuated by a disquieting or ominous reflection on his life as an artist or as a Jew. They led me to think about how his story runs counter to certain mainstream narratives about Jewishness, home, and belonging.

I find that his stories complicate the seemingly light-hearted scenes from his youth, and offer a great deal of context for his tortured self-portraits.