Of Strangers and Slaves

A blog post by Associate Director Tracie Guy-Decker. Read more posts from Tracie by clicking HERE.

On this third day of Passover, I’m thinking a lot about strangers.

I have the great good fortune of being among the inaugural cohort of “community leaders” in the Institute for Islamic, Christian and Jewish Studies (ICJS)’s year-long Imagining Justice in Baltimore initiative. Earlier this month, as a part of this initiative, Rabbi Dr. Marc Gopin did a workshop with the community leaders (there are about 25 of us, each of us an early- or mid-career non-profit professional who self identifies with one of the 3 Abrahamic faiths of the ICJS’s name) and then a public lecture. The title of both was “Imagining Justice in Baltimore: A Jewish Perspective.”

In the several hours I spent in Professor Gopin’s presence, he posited repeatedly that the most important commandment in the Torah is to “love the stranger as yourself.” He pointed out that this commandment appears more than 30 times in the Hebrew Bible. In Gopin’s framework, the significance of loving the stranger (separate from the “neighbor”), is in connecting with the other, whomever that is. He talked about transgressing boundaries, meeting people where they are, honoring the other human being as a human being, regardless of their behavior. For me, his words gave new resonance to that oft-repeated phrase, “love the stranger as yourself.”

Interestingly, especially with this season’s Seders so recent in my memory, each time we are told to love the stranger in the Torah, it is followed by the reminder “for you were strangers in Egypt” (c.f. Leviticus 19:34 for an example). You were strangers in Egypt it says. But as the Seder artfully reminds us through all 5 senses, we weren’t merely strangers in Egypt. We were slaves.

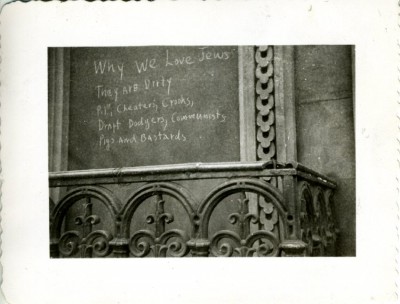

I haven’t fully teased out this idea, but I am becoming more and more certain that the crux of my imagining justice in Baltimore is in the woefully short distance between “stranger” and “slave.”

I believe empathy is the catalyst through which true change comes to human society. The compulsion to comfort, heal, help the other is, in my view, the way the Divine intervenes in human events. That is why Torah reminds us we were strangers in Egypt. That is why the Haggadah enjoins us to imagine we ourselves left Egypt. We are commanded to remember what it feels like. We are commanded to have empathy.

This year, on the fifth day of Passover, the eight-day celebration of our liberation from the land in which we were estranged and enslaved, we will commemorate the anniversary of the moment when individuals and communities who for centuries have been estranged by the system and enslaved by racism, poverty, and mass incarceration, groaned in their suffering and cried out; that stretch of several hours, alternatively called Uprising or Rebellion, when grief and rage erupted in the streets of Baltimore.

As I think about the shifting identity of the stranger and the slave, I cannot help but be struck by the secular drama playing out in the season of our religious-historical drama. Right before Purim, with American electoral politics in mind, I wrote about channeling Esther to find the bravery to stand up to Pharoah. Now that Passover and election day are both upon us, I feel that need ever more strongly.

Passover 5776/2016 falls in the middle of an election season in which fear of the stranger, fear of the other, has become a commodity. The lesson of Passover is that we cannot sit idly by while the stranger becomes the enslaved—we cannot allow the oppression we suffered to be meted out on another. And so we are commanded to repudiate the fear of the stranger and to replace it with love.