Rabbi Morris Lazaron and the Problem of Quotas

Ellen of Baltimore writes, “Your current exhibition [Beyond Chicken Soup: Jews and Medicine in America] is very interesting and extremely well done. I have a question that I wonder if you can answer. Why did Rabbi Lazaron want to stem the tide of Jewish students to medical schools?”

That question had us scratching our heads as well, so in the exhibition’s text panels we fudged. But I recently came across a letter by Rabbi Lazaron that may shed light on the matter.

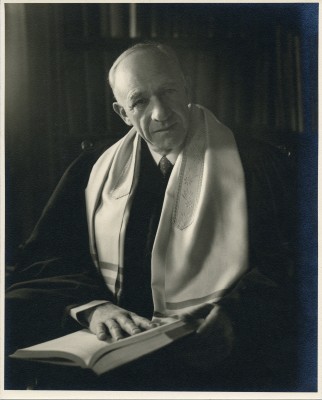

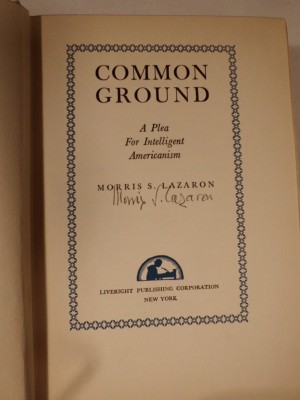

First, a little background, primarily drawn from “The Jewish Problem in U.S. Medical Education, 1920-1955,” by Dr. Edward Halperin, the most authoritative history of the quota system that discriminated against would-be Jewish doctors (excerpt here https://muse.jhu.edu/article/15241/pdf ). This article, published in 2001 by the Journal of the History of Medicine, also alerted us to the role played by Baltimore Hebrew Congregation’s Rabbi Morris Lazaron in documenting the quota system in 1934. Rabbi Lazaron’s papers, held by the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati, which supplied us with hundreds of pages related to his study, and an unpublished thesis by Scott L. Shpeen (A Man Against the Wind: A Biographical Study of Rabbi Morris S. Lazaron, 1984), a copy of which is in the vertical files at the JMM, are the other major sources of information for this post.

Antisemitism in the United States increased throughout the early 20th century as approximately two million Jews came to America, mostly from Eastern and Central Europe. By the time the flow of immigrants was staunched by legislation in 1924, the American-born children of these arrivals were seeking to enter college in large numbers, and “overt anti-Jewish prejudice in the academic community…reached its zenith.” Harvard College president Lawrence Lowell started the ball rolling around 1922 when he suggested that “if every college in the country would take a limited proportion of Jews we should go a long way toward eliminating race feelings among students….” Harvard’s board stopped short of instituting an official policy of quotas, but an unofficial practice of restricted admissions was adopted, and it soon spread to colleges and universities around the country.

The problem was particularly acute in medical schools. In 1927, the dean of the University of Michigan’s medical school concluded that since the school based admission on academic qualifications, and since many applicants with high qualifications were Jews from Eastern Europe (that is, immigrants or children of immigrants), the school was going to be overrun with “undesirables.” What was undesirable about these Jewish students? According to one medical school authority of the day, “it is a fairly tenable fact that…personal acceptability and magnetism…is less prevalent among the Jewish class…than among the entire list of applicants as a whole.”

By the 1930s, about half of all applications to medical schools were coming from Jewish students, but only about 17% of those were accepted. When set against the proportion of Jews in the U.S., then about 3.5%, this number seemed fair to many of the day, including Jews. But the rejected students were complaining and resentment of the quotas—at that time an open secret—was growing. This was the situation when Rabbi Lazaron undertook his extensive investigation. Rabbi Lazaron wrote to the deans of 65 medical schools and received 57 responses.

Rabbi Lazaron wrote to the deans, “I have felt for a number of years that too many of our Jewish students are going into medicine….Personally, I feel that we should not let this matter drift…and that it is the obligation of our Jewish people to attempt to divert, if possible, the increasing flow of Jewish students into this profession.” This is the source of Ellen’s question. Why divert them? How could there be “too many” Jewish doctors? Some colleagues and visitors to the exhibit theorized that Lazaron was showing understanding of the “problem” as a way of encouraging a more honest response from the schools. I believe, on the contrary, that Lazaron’s papers show he meant what he wrote.

For one thing, Lazaron collected a number of articles published in medical journals discussing a concern current in the 1930s over competition between doctors, discussed as “overcrowding” of the medical profession. One Jewish doctor wrote that “seldom does a Jewish physician acquire a clientele among non-Jews.” If Jewish doctors were primarily limited to practicing among America’s tiny percentage of Jews, “an economic problem would arise.” The community might see “a condition of severe competition [that] is conducive to a lowering of ethical standards.”

Another concern may have been the current climate of antisemitism. Hitler had been elected chancellor of Germany in 1933, and American Jews were fearful. In the end, Lazaron decided not to publish his findings, uncertain whether “it would be advisable at the present time to make [this] material a matter of public discussion” (emphasis added). Lazaron did not shrink from talking about being a Jew. In fact, he was a leader in the National Conference of Christians and Jews (founded in 1928), and became nationally prominent in 1933 when he toured the country with Reverend Everett R. Clinchy, a Presbyterian minister, and Father John Ross, a Catholic priest, speaking to audiences about their beliefs and theological differences in an effort to dispel stereotypes. They became known as the “Tolerance Trio.” Lazaron saw his role in teaching Jewish students to cope with prejudice on campuses as particularly important, and while he was passionately committed to his Jewish identity and the right of Jews to worship in distinctive ways, he also sought integration and goodwill.

And this is where the answer may be found. The specter of Jewish competition in the professions, where the stereotype of the “commercial Jew” seemed particularly inappropriate, the need to promote interfaith (and what we might today term inter-cultural) harmony, and perhaps, as Halperin suggests, a personal desire not to upset his own social “apple cart,” all led him to write to the dean of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (who was quite forthright about his school’s quota) that “my chief interest is to present such a picture of the situation as will discourage the flow of Jewish students into medicine.” Further emphasizing the underlying assumption that the push toward medicine was due to commercial considerations, he added “except in such cases where there is conviction of the part of the youth that [medicine] and that alone is his life work.”

As an aside, Lazaron mentions in the same letter that “if I have any energy left after tracking down this material I would like to do the same thing with reference to the number of Jewish students going into law.”

A blog post by Curator Karen Falk. To read more posts from Karen click HERE.

A blog post by Curator Karen Falk. To read more posts from Karen click HERE.