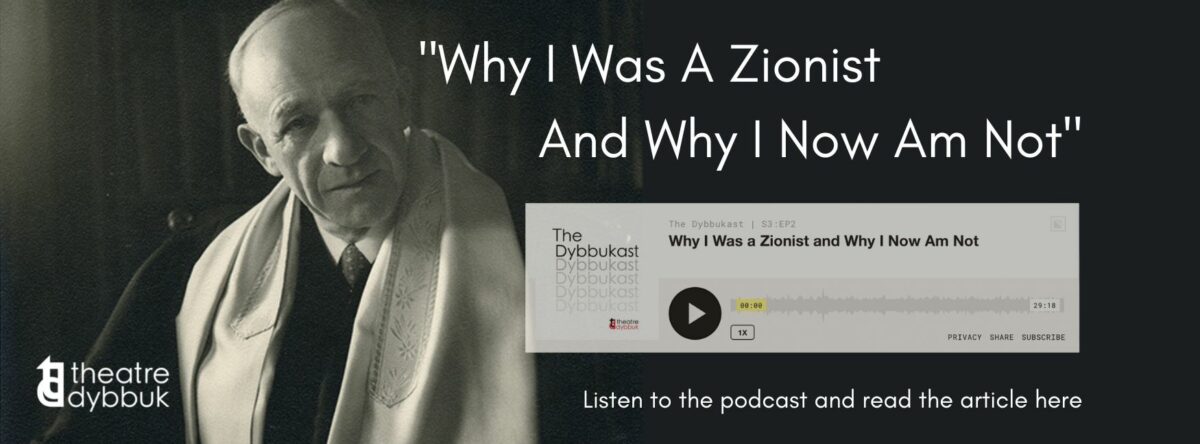

“Why I Was A Zionist And Why I Now Am Not”

by Rabbi Morris S. Lazaron

This article was originally published in the 2007/2008 issue of the Jewish Museum of Maryland’s publication Generations. We are republishing it online in coordination with a new episode of The Dybbukast, Theatre Dybbuk’s podcast, which features the text below and was presented in collaboration with the Jewish Museum of Maryland.

Introduction

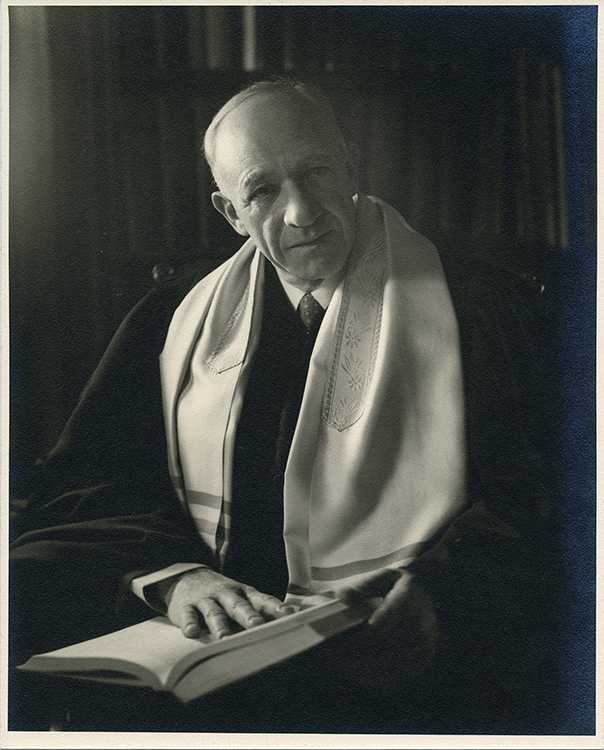

Morris S. Lazaron was born in Savannah, Georgia, in 1888 and lived in that city until he left for Cincinnati, Ohio, where he attended the University of Cincinnati and the Hebrew Union College. He was ordained a rabbi by Hebrew Union College in 1914. After ordination, Rabbi Lazaron served as rabbi of Congregation Leshem Shomayim in Wheeling, West Virginia; in 1915, he accepted the pulpit of Baltimore Hebrew Congregation, where he served as rabbi until 1946 and, later, as Rabbi Emeritus. He died in London, England, in 1979.

While serving in Baltimore, Rabbi Lazaron became nationally known as an advocate for improved Jewish Christian relations. In 1933 and 1935, under the auspices of the National Conference of Christians and Jews, he toured the United States with a Catholic priest and a Protestant minister.² He also published several books, including Seed of Abraham: Ten Jews of the Ages (1930) and Common Ground: A Plea for Intelligent Americanism (1938).

Early in his career, Rabbi Lazaron became an advocate for a Jewish cultural and spiritual homeland in Palestine, but he resisted Jewish nationalism, political Zionism, and the establishment of a Jewish State. In 1942, Rabbi Lazaron was a founder of the American Council for Judaism, an anti-Zionist organization, for which he was a leading ideologue and spokesman. His stance on political Zionism brought Rabbi Lazaron into conflict with many Zionist leaders and, ultimately, his own congregation. As Rabbi Lazaron noted: “My daughter asked her aunt, the wife of a distinguished Zionist leader (Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver), ‘Why do Zionists hate my father so?’ ‘Because he was once a Zionist. But he left the Zionist camp and is now against them. They consider him a traitor. That is why they hate him.’”³

Historian Thomas A. Kolsky summarizes Rabbi Lazaron’s Zionist journey, as follows: “Until the early 1930s, convinced of the peaceful and spiritual nature of Zionism, Lazaron was captivated by the romantic vision of the movement. But his enthusiasm for Zionism Waned at the very time that its general appeal was rising. In the 1930s, he detected a lack of candor in Zionist activities. He felt Zionists were exploiting the Jewish tragedy in Europe for narrow political purposes. Moreover, after visiting Nazi Germany and seeing the effects of its nationalism, Lazaron became convinced that nationalism, a force leading the world to destruction, could not serve as an instrument for Jewish salvation.”⁴

The account printed here is excerpted from Rabbi Lazaron’s unpublished autobiography, with the generous permission of the American Jewish Archives and Dr. Clementine Lazaron Kaufman, Rabbi Lazaron’s daughter and literary executor.

Why I Was a Zionist And Why I Now Am Not

My earliest memory of Zionism dates back to when I was a lad. My parents took me to hear Jacob De Haas lecture in Savannah on the renationalization of the Jew. I sensed at that time a warmth and a glow, which came not only from what he said, but, from the man himself. The Jewish world had been wounded by the Dreyfus trial. In a boyish way I recall sensing some strange organism, far-scattered, numbering millions, that reacted like an individual who had been wounded. The entire organism felt the pain and the shock.

Yet the “affaire” (that is, the infamous Dreyfus affair in France) did not make more than a passing impression on me. Wide family contacts in the community and the rough edges of minority irritation were not close to the surface of American life, particularly in the South. The nation had just won the Spanish-American war. A new era was unfolding. New inventions captured the imagination. There were a sense of power and “going places.” In the early days of the century, vast tides flowing out of the ghettos of Europe- Jews and Gentiles- found shelter here. They were needed to make our clothes, to dig our ditches, to lay our sewage systems, to build our railroads and our highways, to go down into our mines, to man our factories. People were busy in the excitement of their own concerns. And Jews were people.

The most influential Jews were associated in religious activities with the Reform congregations, the American Jewish Committee, and the B’nai Brith. Every city had its “East Side” where the immigrants from Eastern Europe made their home, and the Jews who had been here longer devoted themselves generously to the task of helping their brethren anchor themselves in their new homes and build a new life here.

Under the influence of Dr. Kaufman Kohler, I did not leave Hebrew Union College [in 1914] with any very active, anti-Zionist principles, for though there had been some controversy at the College between Zionism and anti-Zionism- some discussion as to the compatibility of Reform Judaism and Zionism- the issue did not at that time loom very large in the thinking of American Jews. Under the leadership of Isaac M. Wise, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and most of the graduates of the College, as well as the members of the American Jewish Committee and the B’nai Brith-a fraternal organization designed by the older settlers to help the new- were not Zionists or Jewish nationalists. “We are Jews by religion and America is our home, our Zion.” This was not only a slogan; it was a conviction.

I went to Baltimore (in 1915) only moderately non-Zionist. Things happened which disturbed me, challenged my sense of what was right and just and kind. Dr. Max Heller, a leading Reform rabbi who was a Zionist, was refused the pulpit of a Reform congregation. Yet I confess with shame, I was not at that time too deeply disturbed. Stephen S. Wise spoke at the Eutaw Place Temple [in favor of] Zionism. I attended and challenged his position from my seat in the gallery. I have always been puzzled why I did it. I certainly was not trying to create a dramatic situation. My response to what he said was an immediate one, something welling up from the depths of my being. Wise was somewhat taken aback, but responded as only Wise could.

Then came the war, 1914-18. The distress of European Jewry. The campaigns for relief educated the American Jewish community. They certainly broadened my horizons. The Zionists meanwhile had taken full advantage of the situation. The Balfour Declaration was issued, pledging British support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national homeland for the Jewish people.”

Politics were minimized; philanthropy and resettlement emphasized. It was a technique which was to prove completely disarming, effective, and successful.

Zionism insinuated itself into American Jewish life in the guise of philanthropy, and now in these later years it is even more necessary to oppose vigorously its nationalist philosophy expressed in this country under the guise of promoting “Jewishness,” “Jewish unity,” “Jewish education,” and “Democracy in community life.”

I went to Palestine in 1921 with more than an open mind. I was inclined to accept the idea of Palestine as a cultural center. Herzl’s “Judenstaat” seemed only dimly possible of realization. Weizmann’s autobiography clearly shows the strategy which characterized this period of his leadership of the Zionist movement-soft pedal politics in order to get money from American Jews. Talk about “building the Homeland.” Be silent on the State. Weizmann was a shrewd man, with the heart of a politician and the manners of a statesman. But he also possessed great charm which completely disarmed the naive and uninitiated. He knew how to match the argument to the man.

On his first visit to Baltimore, Weizmann asked if he could have a quiet evening; his schedule had been heavy. He dined with Mrs. Lazaron and me. Taking the opportunity for intimate talk, I asked him frankly, “Are you a religious man? I fear the secular emphasis of Jewish nationalism and the alleged irreligion of Zionist leaders. Do you believe in God?”

“Rather than answer directly,” he replied, “I would like to tell you a story. I was in Jerusalem the night after Allenby’s troops marched in. I walked alone to the top of the Mount of Olives, sat on a stone and in the silence looked out over the Holy City. I do not know how long I sat thus. But I had a strange, mystical experience. I seemed to see figures all around me, smiling, encouraging. Instinctively I knew they were the prophets of our people. They uttered words of encouragement and hope. ‘What shall I do!’ I asked them. And a voice said, ‘Do what ben Zakkai did, establish a seat of Jewish learning. That is your first task.”‘ He paused a moment. “That is why the first act of rebuilding the new Palestine was laying the cornerstone of the Hebrew University. This is my answer to your question.”

When the matter of the joint Senate-House Resolution supporting the Balfour Declaration came up for hearing- Fall 1922 -I accepted the invitation of Maryland’s Representative, the late Charles J. Linthicum, to testify. I spoke at that time in favor of the Resolution, making it clear that I was not interested in a Zionist state but in the “Homeland” as refuge and spiritual center.

Some years followed. I began to speak for the Joint Distribution Committee, at one time the greatest effort of private compassion, other than the Red Cross, in the history of man’s will to bind up the wounds of his brothers. Finally moved by motives of sympathy and yielding to the pervasive spell of the phrase, “the peoplehood of Israel,” but without commitment to the political aims of Zionism, I joined the Zionist Organization of America.

Dr. Harry Friedenwald, (an early) President of the Zionist Organization of America and a distinguished oculist of Baltimore, called to see me, to congratulate me. I have not forgotten his words: “You have taken a step the implications of which you may not realize now. It goes deep. It will color your whole outlook.” Shortly thereafter, Justice Brandeis addressed a large Zionist gathering in Baltimore and went out of his way to welcome me personally into the movement. It was heady wine for the young rabbi whose career was yet to be made. I spoke for the Joint Distribution Committee and the Z.O.A. in many cities throughout the country, always in the latter addresses emphasizing Palestine as the cultural homeland and appealing for funds for reconstruction of the land on that basis.

I defined my conception of Jewish nationalism in an address from my own pulpit: “The concept of Jewish peoplehood, ofJewish nationality, has no political or material purpose. It is but the means through which we may perhaps with greater surety fulfill our obligation to be a blessing to the peoples……..The desire for group life is dear to a large proportion of our people. The best opinion in this group dreams to establish gradually, through colonization, a majority population in Palestine and finally to achieve local self-government under the aegis of some power or concert of powers, which shall guarantee them security in life, liberty, and the pursuit of Jewish idealism. They long to build up the ideal society which shall form the pattern for humanity and at the same time will be a dynamic center of Jewish life, sending out its inspiration to scattered Israel, strengthening and heartening him the world over in his consecrated cause to struggle against the forces of injustice and unrighteousness, of superstition and

error…..Local autonomy is all that is desired. This is not in conflict with national loyalty or international comity, nor is it opposed to good citizenship here in America or any other country.”

In my book Seed of Abraham: Ten Jews of the Ages (Century Co. 1930), I included a biography of Herzl and stated my position as follows: “We live in a world of intense nationalisms. The deep unreasoning loyalties of nationalism are used as the motivating force for most of the wars that devastate the- earth and the lives of men. But nationalism cannot be ordered out of the world by the fiat of the Third International. Nationalism is here to stay. It is a force in our civilization which must be reckoned with. We must dominate it or it will dominate us. We can and must spiritualize it.”

“Our present-day world conceives of nationalism, in political terms, in terms of empire and sovereignty. The Jewish conception of nationalism is different. It covets no vast acreage. True it centers on Palestine because of that land’s historic association with the Jewish people. But it is content to make its home there among the Arabs, asking only that it be granted the right to fix the conditions of its own life without interference from or interference with the life of the Arab population. Jewish nationalism seeks the opportunity to express the soul of the Jewish people in terms of institutions, culture, and civilization. This is the new conception of nationalism which the Zionist movement expresses, and which holds a lesson for our world. Nationalism is a spiritual thing; it is not bound up with extensive territory nor boundaries and all the trappings of empire. Nationalism should not express itself in terms of economic aggrandizement and military glory.

“That was the old nationalism. The political and economic aspects of the new nationalism are but the instruments the national idea employs, they are not the end. The end of the new nationalism is the fullest expression of the national soul in the creation of those customs, philosophies and institutions of life which enrich civilization. The old nationalism divided the peoples; the new nationalism will unite them. Out of the very duty and loyalty it demands for itself, will come recognition of the duty and loyalty which each people owes to its own soul. The old nationalism degraded man; the new nationalism will exalt him, because each nation, giving only of its highest and best may ask those things of right from the other. The old nationalism destroyed; the new nationalism will create; it will create the new world which will recognize the reason for difference among the peoples, but will not tolerate jealousy and prejudice and hate based on those differences. The old nationalism made for war; the new nationalism will make for peace.”

I wrote the prayer for the rebuilding of Palestine which is included in the Union Prayer Book, now used by Reform Congregations.

I had not yet realized what Dr. Friedenwald told me, the implications of Jewish nationalism or rather the realities of the Jewish nationalist world movement.

Disillusionment came gradually. But persistent doubts beat upon my mind. The Zionist leaders seemed to be less than completely frank in their discussions with those from whom they desired contributions. What they said to these men differed from what I heard them say when speaking at purely Zionist gatherings and from what I read in the Zionist press. They talked about the democratization of Jewish life and yet the party lines and discipline were in the hands of a few who exercised an autocratic authority which no one could challenge. I began to feel there was no democracy in the movement. During the controver sies between the American Jewish Committee and the Joint Distribution Committee on the one hand and the Zionist Organization of America on the other, I wrote and pleaded for honorable compromise between the two factions, for unity in American Jewish life.

I saw evasion, chicanery, misrepresentation of facts, and above all the most unseemly methods in controversy which indulged in cheap and vulgar epithets, rather than that calm appraisal which should characterize the discussion of such important issues.

Finally I came to the conclusion that the Zionists were using Jewish need to exploit their political goals. Every sacred feeling of the Jew, every instinct of humanity, every deep-rooted anxiety for family, every cherished memory became an instrument to be used for the promotion of the Zionist cause. If you were not with the Zionists, ipso facto, you were against them. When these convictions crystallized after a few years, I withdrew from the organization.

Meanwhile the Nazi persecutions began. American Jews were frantic in their determination to help their brethren. I made two trips to Germany in 1934 and in 1935, the latter at the request of Jewish leaders in New York. I spent nearly six months in Hitler’s Germany, one of the most unhappy periods of my life. I went with the dim hope to be able to ameliorate in some measure the affliction of my brethren. The effort had the support of the State Department and the cooperation of Ambassador Dodd. Perhaps we should have known it would be a forlorn and futile hope.

The Zionists and Jewish nationalists at home pounded away at the theme: no place but Palestine. The impact of the tragedy as the months went by, the desperate anxiety to do what could be done, had their effect on the United Jewish Appeal for funds. Under Zionist pressures, the allocations for Palestine became larger and larger, for the relief work of the Joint Distribution Committee, smaller and smaller.

Meantime the philosophy of life, which was in my judgment the only basis for healthy Jewish living in the United States, came under fire. It was said the fate of German Jewry indicated the futility of “assimilation,” that is, the desire of Jews to live among their fellow citizens anywhere as members of a religious group only and with no other barriers setting them apart, save the tie of their common faith, Judaism. The Jewish nationalist philosophy of separateness as a people who would always and inevitably be rejected because they were Jews, boldly asserted itself. The idea seems to have been to break down the self-confidence of American Jews, to make them believe because emancipation (the entering of the Jew into full rights, privileges, and duties of citizenship) had failed in Germany, their only recourse was to unite Jewry though scattered throughout the world into one people. (Zionism viewed Jewry as) landless for the moment through the exigencies of history, but conscious of its unique unity and determined to act together in the United States and throughout the world as a political pressure unit. The determination to capture the American Jewish community, to dominate it and use it for Zionist political aims, which Herzl had declared to be necessary, became the avowed goal of the American Zionists.

I then turned to forthright opposition to Jewish political nationalism. I stated the case, as I saw it, in an address before the Union of American Hebrew Congregation’s annual convention in New Orleans, January 1937. “The cruel fate of our people particularly in Germany, together with the rise of nationalism, has moved a number of Jewish leaders, veterans in the Jewish cause, to lift the banner of Jewish nationalism. They say two things: 1. the plight of German Jewry shows the failure of the emancipation-and I take mancipation to mean not suicide but integration in the life of the nation where the Jew makes his home; 2. The only hope for the Jew is the development everywhere of an intense Jewish nationalism which centers in Palestine.

“I deny both assertions. To declare that German Jewry was assimilated; that it sold its birthright; that it consciously attempted to lose its identity is not true. It is a libel upon the noble institutions and the rich creative literary, scholarly, and artistic Jewish life of pre-Hitler Germany.

“To follow this libel with the further assertion: you see what happened-they tried and they failed; therefore, integration everywhere is doomed to failure is to add misrepresentation to libel…It is naive to believe that any simple formula will solve all our Jewish difficulties. I yield to no one, not even to the officials of the Zionist Organization of America, in my disinterested loyalty to Palestine reconstruction. I have worked for it, and pleaded for it, and I shall continue to do so. But Jewish nationalists are doing the same damage to Palestine reconstruction that the uncompromising pacifists and the proponents of unilateral disarmament are doing to the cause of peace. Over-emphasis upon the political aspects of the situation runs right up against two inexorable factors that cannot be argued away-Arab nationalism and British Imperial policy on the other hand. A yishub of 400,000 souls is an economic magnet whose ordinary needs, with the help which Jews throughout the world are prepared to give, will bring it normal healthy growth…

“I believe in rebuilding the ancient homeland both from the philanthropic and the cultural points of view. My life has been made richer because I have been privileged to serve humbly in that cause. I, too, have drunk with my people our common cup of bitterness. But that diaspora nationalism, which is implicit in the American Jewish Congress’ Zionist idea, is a Chukoth ha-Goyim, an imitation of the Gentiles. Behind the mask of Jewish sentiment, one can see the specter of the foul thing which moves Germany and Italy. Behind the camouflage of its unquestioned appeal to Jewish feeling, one can hear a chorus of ‘Heil:’ This is not for Jews- Reform, Conservative or Orthodox. Has the time not come for us emphatically and publicly to repudiate that group which calls long and loud for Jewish unity but attacks all other Jewish organizations in American life and refuses to cooperate with them, except on its own terms; which prates of democratic control and is dominated by imitation Jewish Fuehrers; which stirs up class feeling among Jews to further its own purposes; and which in its Bulletin of January 1, presumes to speak through its World Congress–a grandiose misnomer for the Jews of the world. It does not speak for you, and it does not speak for me. It does not speak for the majority of the Jews in our country, Reform, Conservative and Orthodox. It is still a pathetic minority and its bluff should be called…

“We may not like the burden which history and our tradition lay upon us. We may rebel against it, but there it is and we Jews deny it to our peril. We are ‘am segullah‘-an unique people. Others say, ‘Save the Jewish people’ Yes, but I am not interested in saving the Jewish people as a people except In their hearts there burn the fires of the old faith, the psalmists’ longing for God, the prophets’ social passion and the rabbinical challenge to life’s disciplines. Let us first secure the dignity of our own souls by the method tried and tested through the centuries- ennenu am ki im betorah [we are a people only through Torah]!

“Judaism cannot accept as the instrument of its salvation the very philosophy of nationalism which is leading the world to destruction. Shall we condemn it as Italian or German, but accept it as Jewish? Innately we recognize and proudly yield to our sense of Jewish brotherhood throughout the world. Two leitmotifs thread their golden melody through our history: People and God, God and People. God claims us, we claim God. Down through the centuries comes my people, glorious weak one, pathetic hero whom the cruel holiness of God has claimed for its own. The tie that binds us, while compounded of many elements, is primarily and fundamentally our Judaism. It has been so in the past-it is so today.”

One of my colleagues, a Zionist leader, came up to me afterward and with a far from rabbinical expletive angrily said, “You ________, you did this just when we were beginning to have things so well in hand.”

Epilogue

Rabbi Lazaron remained a staunch proponent of Palestine as a place of refuge and as a center for Jewish spiritual and cultural life. But his opposition to political Zionism and to the establishment of a Jewish State intensified.

In 1942, the anti-Zionist movement established an organization, the American Council for Judaism (ACJ). In June, thirty-six Reform rabbis, anxious to maintain the Reform movement’s universalistic values and opposed to a narrowly defined political Zionism, met in Atlantic City. At this meeting, Rabbi Lazaron opposed “secular Jewish nationalism,” but warned his colleagues that “opposition to a Jewish state needed to be coupled with support for relief and resettlement work in Palestine and elsewhere.”⁵

The rabbinic group issued a statement in August 1942 in which they acknowledged the importance of Palestine “to the Jewish soul,” but rejected political Zionism. Instead, they argued, Reform Jews and the Reform movement should be devoted to “the eternal prophetic principles of life and thought, principles through which alone Judaism and the Jew can hope to endure and bear witness to the universal God.”⁶ This manifesto ignited a firestorm of attacks from Zionist leaders and the Jewish press, including a statement issued by 757 Zionist rabbis titled “Zionism: An Affirmation of Judaism.”⁷

Although leadership of the American Council for Judaism soon shifted from its originating rabbinic group to powerful lay leaders, Rabbi Lazaron remained one of its inner circle and one of the Council’s foremost spokesmen. From 1943 through 1948, the Council issued several statements of principle and policy. The arguments put forward by the AJC included:

- Any hopeful future for Jews in Palestine depends upon the ultimate establishment of a democratic government there, in which Jews, Muslims and Christians shall be justly represented (August 1943).

- The Holy Places (should be) internationalized (October 1947).

- Nationality and religion are separate and distinct. Our nationality is American. Our religion is Judaism. Our homeland is the United States of America. We reject any concept that Jews are at home only in Palestine (January 1948).⁸

In May 1948, the establishment of the new State of Israel effectively ended the debate between Zionists and anti-Zionists within American Jewry. Although support for the ACJ plummeted, it survives to this day, promoting its vision of Judaism as “a universal religious faith, rather than an ethnic or nationalist identity.”⁹ The debates it helped to fuel in the years leading up to statehood continue to resonate in the contemporary world.

A Prayer for Zion

Rabbi Lazaron wrote the following prayer for the Reform movement prayer book. Like his public speeches, this prayer emphasizes Israel’s spiritual mission and Zion’s role as a source of Divine inspiration.

Uphold also the hands of our brothers who toil to rebuild Zion. In their pilgrimage among the nations, Thy people have always turned in love to the land where Israel was born, where our prophets taught their imperishable message of justice and brotherhood and where our psalmists sang their deathless songs of love for Thee and of Thy love for us and all humanity. Ever enshrined in the hearts of Israel was the hope that Zion might be restored, not for their own pride or vainglory, but as a living witness to the truth of Thy word which shall lead nations to the reign of peace. Grant us strength that with Thy help we may bring a new light to shine upon Zion. Imbue us who live in lands of freedom with a sense of Israel’s spiritual unity that we may share joyously in the work of redemption so that from Zion shall go forth the law and the word of God from Jerusalem.

-Union Prayer Book, 1940

Notes

- ”An Inventory to the Morris S, Lazaron Papers, Manuscript Collection No. 71, 1888-1979,” Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati. See www.americanjewisharchives.org/aja/Finding Aids/Lazaron.htm, 1-2.

- Ibid.

- Rabbi Morris S. Lazaron, “Autobiography,”Morris S. Lazaron Papers, Box 31.

- Thomas A. Kolsky, Jews against Zionism: The American Council for Judaism, 1942-1948 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980), 43.

- Kolsky, Jews against Zionism, 50. See also Thomas A. Kolsky, “The Opposition to Zionism: The American Council for Judaism Under the Leadership of Rabbi Louis Wolsey and Lessing Rosenwald,” in Murray Friedman, ed., Philadelphia Jewish Life, 1940-2000 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press,2003), 43.

- Kolsky, Jews against Zionism, 54.

- Ibid., 54f.

- Quoted in Kolsky, “The Opposition to Zionism,” 47; Kolsky, Jews against Zionism.

- From the American Council for Judaism website, acjna.org/acjna/about_principles.aspx, accessed November 12, 2009.