Two Lives in Labor: Jacob Edelman Part 2

Edited by Avi Y. Decter. Originally published in Generations 2009-2010: 50th Anniversary Double Issue: The Search for Social Justice.

The account of Jacob Edelman’s early years in the labor movement comes from an oral history conducted by Bertha Libauer on November 2, 1975.

Part II: A New Era

Miss part 1: The Voice of Labor?

I left Baltimore and went to New York because in order to get a job in another plant whether it would be Schloss Bros. or Henry Sonneborn & Co. they knew that we were involved in a strike, and they knew we were very much involved and couldn’t get a job. The only thing I could do was to go to New York. New York was already a lot different. New York was the so-called cradle of “Industrial Civilization.” New York was the reservoir of unionism. I went to the union office there, identified myself, and why I had to leave Baltimore, and I was given a job. New York opened all sorts of avenues for me that I would never have had in Baltimore.

I earned my living of twelve dollars a week in the cutting department, and at that time I worked forty-eight hours instead of fifty-six in Baltimore. And we had recognition of the union, and we had meetings in the union–open without secreting your identity, you had shop stewards in the shops, you had committees if you had a grievance, foremen treated you with much more dignity than what I was accustomed to here, and so it gave me opportunities to do things in addition to working in the plant and maintaining myself. I enrolled in the Cooper Union School of Social Science, and there I took economics.

I spent in New York from the end of 1913 to the beginning of 1916, keeping in touch with my sisters, slipping into Baltimore to see them, going back to New York. They were happy to see how I looked and that I was getting along. I was beginning to hear a lot of music in New York, going to the Metropolitan, symphonies, concerts, etc. New York had what was good for my soul as for the body.

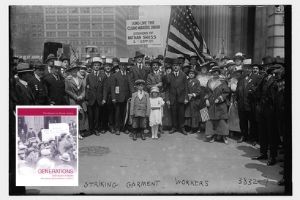

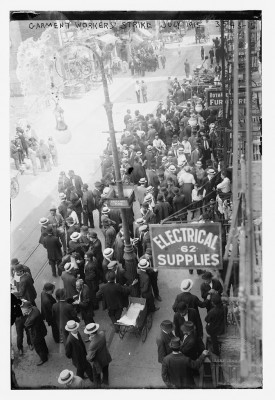

Then there came a new era in the labor movement. There was the upsurge in leadership upon the American scene. [Sidney] Hillman became the first president of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. When that organization came upon the scene, it supplanted the United Garment Workers. It was like civil war within the labor movement as to which would predominate and which would survive. The masses of the people clung to the Amalgamated because that was the new liberal spirit that permeated and influenced the garment industry. It was almost like a sister organization to the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, which dealt with ladies’ wearing apparel. The leadership was of the same philosophical pattern. They were all people who had come from the other side. They witnessed industrial exploitation, political oppression and came to this country and assumed their position in this free country, that was dearest to their hearts and that was human freedom and human dignity and better working conditions and to establish a sort of Bill of Rights to the people in industry.

That’s when I came back to Baltimore. I became involved in the Amalgamated, and before long I was on its staff. I became a leader of the cutters. They had crafts–they had coat makers locals, pants makers locals, finishers locals. The finishers were women buttonhole makers–all women, wonderful crafts-people, who were doing delicate kinds of work. They were segregated into various locals, known as the craft locals. I was, of course, in the cutters craft. There it was a democracy, you were not appointed nor were you anointed a leader. You had to be elected by the people and so democracy was in action on the industrial level, vis-a-vis the labor movement. I was elected a business agent and representative of the cutters craft under the Amalgamated leadership.

The labor movement was engaged in various struggles with the captains of industry. As unions were coming in conflict with industry, they wound up in the courts. Often lock-outs, strikes, injunctions, arrests, convictions–unions needed lawyers. They needed defenders and advocates. The leadership contained in their own right advocacy, but they need legal advocates and you needed legal defenders, people within the labor movement who became involved in litigation with industry.

At that time I found a position in the Amalgamated, I was free to be able to study, attended Hopkins to take classes, attended the YMCA Day School to prepare myself for admission to the University of Maryland, and after that, in 1921 until 1925 I received a law degree as Bachelor of Laws & Letters. I took my examination, passed the bar and became a lawyer, and that’s when I began to represent labor to the exclusion of any other economic interest until this day.

I was naturally identified as representing labor, which was not very fashionable, because most lawyers in the profession were fearful to represent labor’s interests because it was a disadvantage to a lawyer who was naturally a general practitioner and if he undertook to represent a labor union, he would lose [clients], because they were not pro-labor minded, they were business men, they were manufacturers, they were industrialists and they would not have any truck with a lawyer who attempts to represent labor. These upstarts were not satisfied with conditions with the status quo. They were rebelling against the establishment. So if you represented labor, you were a labor lawyer, and there were many lean years when labor did not have the wherewithal to compensate a lawyer. You had to be thoroughly dedicated to that cause, otherwise you couldn’t serve labor.

And then labor came into its own. Then came the terrible depression, the Roosevelt Administration. The tremendous upsurge of the CIO. In this city I was the pioneer, the sole and only lawyer at the bar who represented labor’s interests, who understood labor’s problems and at the same time attained an attitude of an even balance because I was taught by Sidney Hillman, and that I will never forget, a man who was a great scholar, a man who was destined to be a rabbi but came over to the side of the rebels to lead masses to effect their economic social and political well being. He taught those of us that were close to him– “In your dealings with employers you must remember and not forget that if you drag the employer down you drive yourself under and under is lower than down, so make sure that in your dealings with employers you must always have a healthy economic employer who will be able to give you what is reasonable for you to receive.” This is the school of labor relations in my time. By these standards I maintained my professional approach in representing labor’s interests.

As much as can be said that labor [today] can be found unreasonable in its demands, the leadership of American industry has in its history, failed to recognize the rights of labor in their days, so that you have a constant clash and conflict between labor and industry, and also labor and capital. If labor had waited, without establishing itself through its own strength, and through its own might and main to demand and secure certain rights, they would have never been given to labor, and that goes for legislation as well. If you turn the clock back about sixty years ago, there was no such thing as workmen’s compensation. If a person lost his life in the line of duty, the widow and children were helpless. If he lost a limb or an eye or what-not, there was no such thing. What would have been the history of this country without the labor movement?

Continue to Part III: We Will Begin the Campaign (Sarah Barron)